280+ Robust Verbs: three Tricks to Strengthen Your Verbs in Writing

Strong verbs transform your writing from drab, monotonous, unclear, and amateurish to engaging, professional, and emotionally powerful.

Which is all to say, if you’re not using strong verbs in your writing, you’re missing one of the most important stylistic techniques.

Why listen to Joe? I’ve been a professional writer for more than a decade, writing in various different formats and styles. I’ve written formal nonfiction books, descriptive novels, humorous memoir chapters, and conversational but informative online articles (like this one!).

Which is all to say, I earn a living in part by writing (and revising) using strong verbs selected for each type of writing I work on. I hope you find the tips on verbs below useful! And if you want to skip straight to the verb list below, click here to see over 200 strong verbs.

Hemingway clung to a writing rule that said, “Use vigorous English.” In fact, Hemingway was more likely to use verbs than any other part of speech, far more than typical writing, according to LitCharts:

But what are strong verbs? And how do you avoid weak ones?

In this post, you’ll learn the three best techniques to find weak verbs in your writing and replace them with strong ones. We’ll also look at a list of the strongest verbs for each type of writing, including the strongest verbs to use.

What are Strong Verbs?

Strong verbs, in a stylistic sense, are powerful verbs that are specific and vivid verbs. They are most often in active voice and communicate action precisely.

The Strongest Verbs

Writers will use descriptive verbs that best fit their character, story, and style, but it’s interesting to note trends.

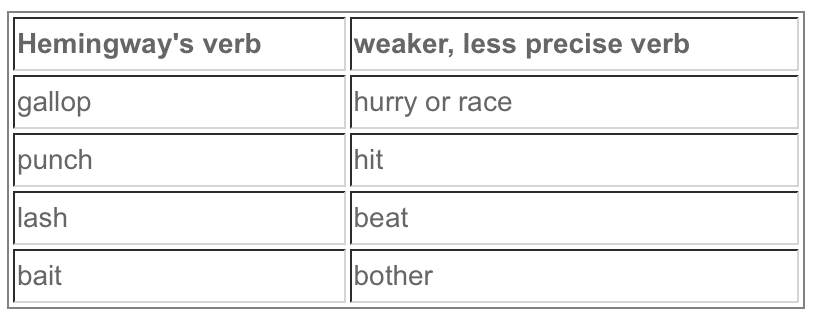

For example, Hemingway most often used verbs like: galloped, punched, lashed, and baited. Each of these verbs evokes a specific motion, as well as a tone. Consider how Hemingway’s verbs stack up against weaker counterparts:

None of the weaker verbs are incorrect, but they don’t pack the power of Hemingway’s strong action verbs, especially for his story lines, characters, and style. These are verbs that are forward-moving and aggressive in tone. (Like his characters!)

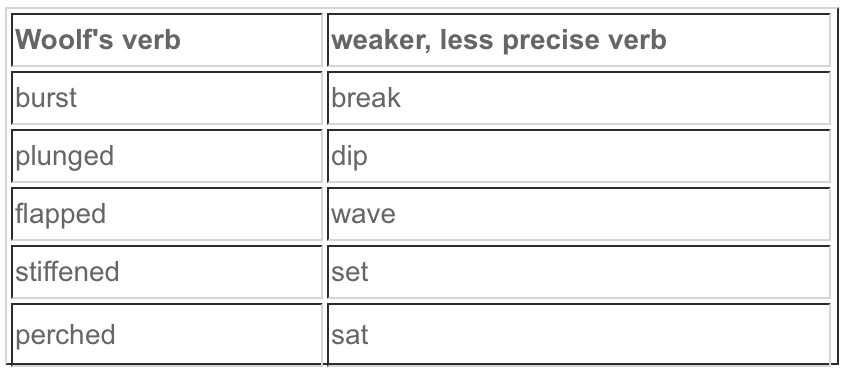

Consider how those choices differ significantly than a few from Virginia Woolf’s opening page of Mrs. Dalloway:

Notice how Woolf’s choices create the vibrant, descriptive style that marks her experimental novel and its main character. Consider the difference between “perched” and “sat.” “Perched” suggests an image of a bird, balancing on a wire. Applied to people, it connotes an anxiousness or readiness to stand again. “Sat” is much less specific.

The strongest verbs for your own writing will depend on a few things: your story, the main character, the genre, and the style that is uniquely yours. How do you choose then? Let’s look at three tips to edit out weak, boring verbs.

How to Edit for Strong Verbs FAST

So how do you root out those weak verbs and revise them quickly? Here are a few tips.

1. Search for Weak Verbs

All verbs can be strong if they’re used in specific, detailed, and descriptive sentences.

The issue comes when verbs are overused, doing more work than they’re intended for, watering down the writing.

Here are some verbs that tend to weaken your writing:

- is

- was

- am

- were

- being

- are

- get

- got

- have

- had

Did you notice that most of these are “to be” verbs? That’s because “to be” verbs are linking verbs or state of being verbs. Their purpose is to describe conditions.

For example, in the sentence “They are happy,” the verb “are” is used to describe the state of the subject.

There’s nothing particularly wrong with linking verbs. Writers who have a reputation for strong writing, like Ernest Hemingway or Cormac McCarthy, use linking verbs constantly.

The problem comes when you overuse them. Linking verbs tend to involve more telling vs. showing.

Strong verbs, on the other hand, are usually action verbs, like whack, said, ran, lassoed, and spit (see more in the list below).

The most important thing is to use the best verb for the context, while emphasizing specific, important details.

Take a look at the following example early into Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls:

The young man, who was studying the country, took his glasses from the pocket of his faded, khaki flannel shirt, wiped the lenses with a handkerchief, screwed the eyepieces around until the boards of the mill showed suddenly clearly and he saw the wooden bench beside the door; the huge pile of sawdust that rose behind the open shed where the circular saw was, and a stretch of the flume that brought the logs down from the mountainside on the other bank of the stream.

I’ve highlighted all the verbs. You can see here that Hemingway does use the word “was,” but most of the verbs are action verbs, wiped, took, screwed, saw, etc. The result of this single sentence is that the audience pictures the scene with perfect clarity.

Here’s another example from Naomi Novick’s Deadly Education:

He was only a few steps from my desk chair, still hunched panting over the bubbling purplish smear of the soul-eater that was now steadily oozing into the narrow cracks between the floor tiles, the better to spread all over my room. The fading incandescence on his hands was illuminating his face, not an extraordinary face or anything: he had a big beaky nose that would maybe be dramatic one day when the rest of his face caught up, but for now wasjust too large, and his forehead was dripping sweat and plastered with his silver-grey hair that he hadn’t cut for three weeks too long.

Vivid right? You can see that again, she incorporates weaker verbs (was, had) into her writing, but the majority are highly descriptive action verbs like hunched, illuminating, spread, plastered, and dripping.

Don’t be afraid of linking verbs, state verbs, or helping verbs, but emphasize action words to make your writing more powerful.

2. Remove Adverbs and Replace the Verbs to Make Them Stronger

Adverbs add more detail and qualifications to verbs or adjectives. You can spot them because they usually end in “-ly,” like the word “usually” in this sentence, or frequently, readily, happily, etc.

Adverbs get a bad rap from writers.

“I believe the road to hell is paved with adverbs,” Stephen King said.

“Adverbs are dead to me. They cannot excite me,” said Mark Twain.

“I was taught to distrust adjectives,” said Hemingway, “as I would later learn to distrust certain people in certain situations.”

Even Voltaire jumped in on the adverb dogpile, saying, “Adjectives are frequently the greatest enemy of the substantive.”

All of these writers, though, used adverbs when necessary. Still, the average writer uses them far more than they did.

Adverbs signal weak verbs. After all, why use two words, an adverb and a verb, when one strong verb can do.

Look at the following examples of adverbs with weak verbs replaced by stronger verbs:

- He ran quickly –> He sprinted

- She said loudly –> She shouted

- He ate hungrily –> He devoured his meal

- They talked quietly –> They whispered

Strive for simple, strong, clear language over padding your writing with more words.

You don’t need to completely remove adverbs from your writing. Hemingway himself used them frequently. But cultivating a healthy distrust of adverbs seems to be a sign of wisdom among writers.

“

Strive for simple, strong, clear language using strong verbs over padding your writing with more words. Check it out in this article.

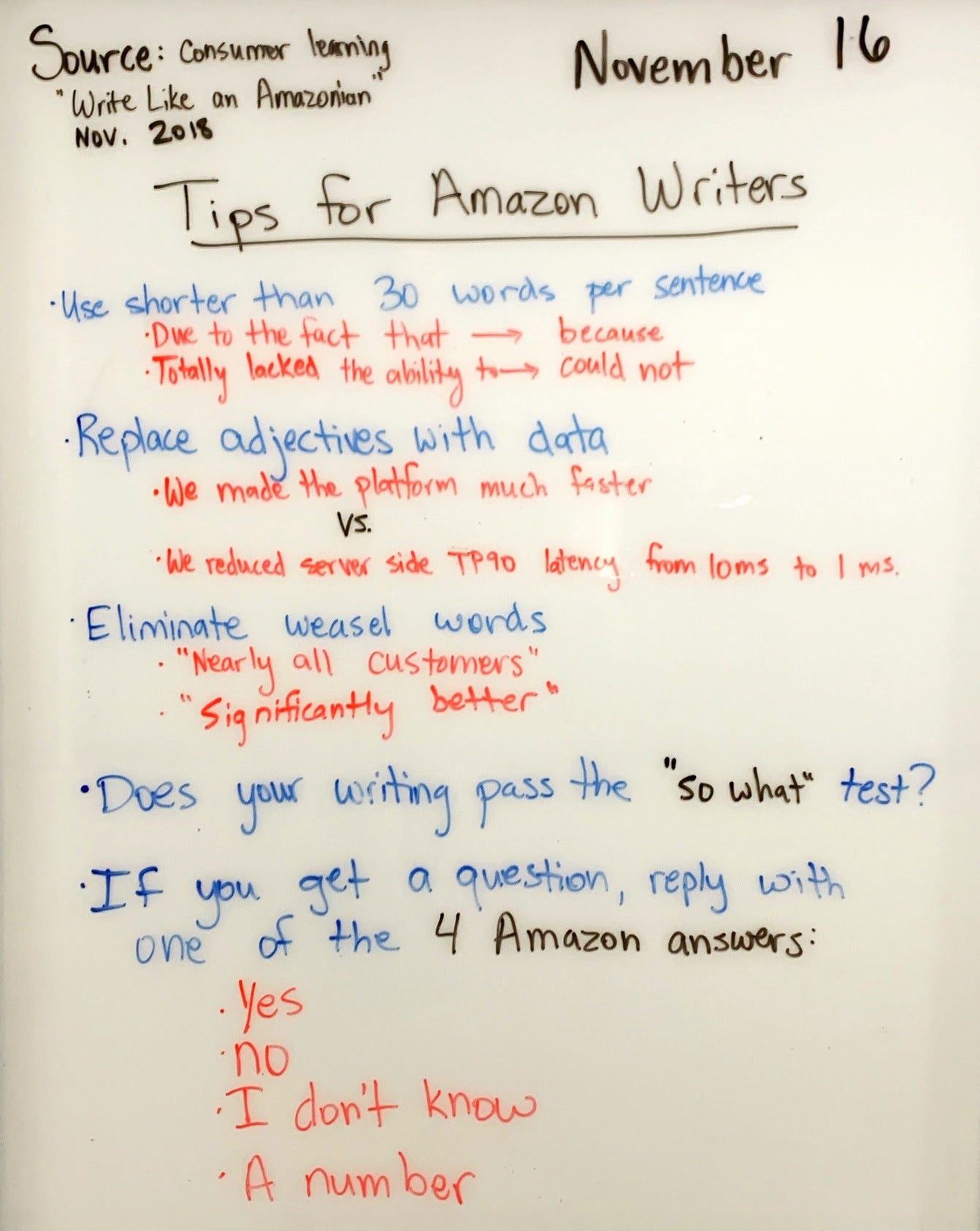

3. Stop Hedging and “Eliminate Weasel Words”

Amazon’s third tip for writing for employees is “Eliminate Weasel Words,” and that advice applies to verbs too.

Instead of “nearly all customers,” say, “89 percent of customers.”

Instead of “significantly better,” say, “a 43 percent improvement.”

Weasel words are a form of hedging.

Hedging allows you to avoid commitment by using qualifiers such as “probably,” “maybe,” “sometimes,” “often,” “nearly always,” “I think,” “It seems,” and so on.

Hedge words or phrases soften the impact of a statement or to reduce the level of commitment to the statement’s accuracy.

By eliminating hedging, you’re forced to strengthen all your language, including verbs.

What do you really think about something? Don’t say, “I think.” Stand by it. A thing is or isn’t. You don’t think it is or believe it is. You stand by it.

If you write courageously with strength of opinion, your verbs grow stronger as well.

Beware the Thesaurus: Strong Verbs are Simple Verbs

I caveat this advice with the advice to beware thesauruses.

Strong writing is almost always simple writing.

Writers who replace verbs like “was” and “get” with long, five-syllable verbs that mean the same thing as a simple, one-syllable verb don’t actually communicate more clearly.

To prepare for this article, I studied the verb use in the first chapters of several books by my favorite authors, including Ernest Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls and Naomi Novik’s Deadly Education.

Hemingway has a bigger reputation as a stylist and a “great” writer, but I found that Novik’s verb choice was just as strong and even slightly more varied.

Hemingway tended to use simpler, shorter verbs, though, often repeating verbs, whereas Novik’s verbs were longer and often more varied.

I love both of these writers, but if you’re measuring strength, simplicity will most often win.

In dialogue this is especially important. Writers sometimes try to find every synonym for the word, “said” to describe the exact timber and attitude of how a character is speaking.

This becomes a distraction from the dialogue itself. In dialogue, the words spoken should speak for themselves, not whatever synonym the writer has looked up for “said.”

Writers should use simple speaker tags like “said” and “asked” as a rule, only varying that occasionally when the situation warrants it.

270+ Strong Verbs List

We’ve argued strong verbs are detailed, descriptive, action verbs, and below, I list over 200 strong verbs to make your writing better.

“

If you’re looking to make your writing stronger, clearer, and more precise, start with revising your verbs. Check out this list of over 280 strong verbs to try.

I compiled this list directly from the first chapters of some of my favorite books, already mentioned previously, For Whom the Bell Tolls by Ernest Hemingway, Deadly Education by Naomi Novik, and The Undoing Project by Michael Lewis.

This is a necessarily simplified list, taken only from the first chapters of those books. There are thousands of strong verbs, usually action verbs, but these are a good start.

I’ve also sorted them alphabetically and put them into present tense.

- Accomplish

- Acquire

- Adjust

- Advise

- Aim

- Allow

- Analyze

- Answer

- Appear

- Apply

- Approach

- Argue

- Arm

- Arrest

- Arrive

- Assume

- Audition

- Avoid

- Back out

- Band

- Become

- Believe

- Bill

- Blink

- Block

- Bother

- Breathe

- Bring

- Build

- Burn

- Burst

- Buy

- Call

- Care

- Carry

- Catch

- Cave

- Change

- Charge

- Chase

- Check

- Claw

- Clean

- Clear

- Collect

- Collaborate

- Come

- Command

- Compare

- Conceive

- Consign

- Contain

- Count

- Cross

- Cultivate

- Cut

- Dance

- Decide

- Depend

- Determine

- Die

- Dig

- Dismiss

- Dismount

- Discover

- Dissolve

- Drink

- Drive

- Drop

- Drip

- Dump

- Eat

- Encourage

- Engage

- Enjoy

- Envelope

- Evaluate

- Expect

- Explain

- Expose

- Fail

- Fall

- Feign

- Feed

- Feel

- Figure out

- Fill

- Finish

- Flag

- Flip

- Fly

- Force

- Fool

- Fumble

- Gather

- Gas

- Give

- Go

- Grab

- Graduate

- Grill

- Grin

- Grow

- Guess

- Hand

- Happen

- Hear

- Help

- Hiccup

- Hire

- Hiss

- Hold

- Hunch

- Hunt

- Indicate

- Influence

- Install

- Intellectualize

- Interview

- Invent

- Jam

- Jerk

- Join

- Jolt

- Judge

- Keep

- Kill

- Knock

- Know

- Latch

- Lead

- Lean

- Leave

- Let

- Lie

- Lift

- Like

- Linger

- Live

- Load

- Look

- Love

- Lower

- Lull

- Make

- Manage

- Measure

- Meditate

- Miss

- Mislead

- Move

- Murder

- Mistrust

- Need

- Nod

- Notice

- Offer

- Operate

- Ooze

- Own

- Pack

- Pass

- Pay

- Penetrate

- Perform

- Pick

- Pick up

- Pin

- Place

- Plan

- Point

- Popularize

- Pray

- Predict

- Pretend

- Promise

- Pronounce

- Prove

- Protect

- Protest

- Pull

- Push

- Quit

- Ratchet

- Read

- Realize

- Receive

- Refer

- Rely

- Remember

- Render

- Repair

- Replace

- Resist

- Retire

- Revert

- Ride

- Rise

- Raze

- Rope

- Rot

- Run

- Sacrifice

- Sail

- Saddle

- Save

- Say

- Scrape

- Score

- Scoop

- Screw up

- See

- Seem

- Send

- Set

- Set out

- Settle

- Shake

- Shape

- Shove

- Show

- Shut

- Slaughter

- Sleep

- Slither

- Smile

- Sneak

- Sort

- Speak

- Spend

- Spit

- Spread

- Stand

- Start

- Stay

- Steal

- Stop

- Store

- Straighten

- Stride

- Struggle

- Stagger

- Suck

- Summon

- Swing

- Take

- Talk

- Tease

- Tell

- Test

- Think

- Throw

- Touch

- Track

- Transfer

- Travel

- Trigger

- Trust

- Turn

- Understand

- Undertake

- Unearth

- Use

- Vanish

- Walk

- Wander

- Wash

- Watch

- Wear

- Weigh

- Whack

- Whinny

- Whip

- Wonder

- Work

- Worry

- Write

- Yell

- Yank

The Best Way to Learn to Use Strong Verbs

The above tips will help get you started using strong verbs, but the best way to learn how to grow as a writer with your verbs is through reading.

But not just reading, studying the work of your favorite writers carefully and then trying to emulate it, especially in the genre you write in.

As Cormac McCarthy, who passed away recently, said, “The unfortunate truth is that books are made from books.”

If you want to grow as a writer, start with the books you love. Then adapt your style from there.

PRACTICE

Choose one of the following three practice exercises:

1. Study the verb use in the first chapter of one of your favorite books. Write down all of the verbs the author uses. Roughly what percentage are action verbs versus linking verbs? What else do you notice about their verb choice?

2. Free write for fifteen minutes using only action verbs and avoiding all “to be” verbs and adverbs.

3. Edit a piece that you’ve written, replacing the majority of linking verbs with action verbs and adverbs with stronger verbs.

Share your practice in the Pro Practice Workshop here, and give feedback to a few other writers.