How one can Write a Screenplay: The 5 Step Course of

Have you ever wondered how to write a screenplay? Have you fantasized about writing a Hollywood movie or, with a bit of luck, creating the next great TV series?

In a visual age, with the decline of traditional publishing, you might look to script writing as a way to create the “literature of the future.”

But what is the process of writing a screenplay? How do you even begin? And why is it important to know how writing films are different, but also can be similar, to writing a novel?

In this post we’re going to look at the five step process professional screenwriters use to write a screenplay.

Learn how to write a movie script that filmmakers—and an audience—loves!

FADE IN:

Why I’m Thinking About Writing a Screenplay

Earlier this week, a friend who’s a lawyer approached me about a writing opportunity. He was closing a tragic but fascinating case, and he thought it had potential to be a major film.

At first, I shrugged it off.

Screenplays are like books: everyone thinks they have one in them. But then he told me the story, and it was awesome—a family’s search for the American dream, drug dealers under the scrutiny of the law, police corruption, an adrenaline powered shooting, everything you could want in a major motion picture.

Still, I held back.

The hardest part of making a movie isn’t writing a good movie script. It’s getting someone to fund the process of bringing the story to life (do you have a hundred million dollars lying around to fund a movie?).

Fortunately, said the lawyer, he’s friends with several people at a major Hollywood studio. He told me, “We have everything we need . . . except for a great screenplay.”

“Hmm . . .” I thought. “Maybe this isn’t a complete waste of time.”

In my experience, most writing projects like this don’t work out, but when they show up, it’s important to give them your best.

After all, at the very least, it’s good writing practice. And, like always, practice is always good for your writing process.

Are you thinking of writing a screenplay? Check out Oscar winner and TV hitmaker (The West Wing) Aaron Sorkin’s masterclass.

How I Learned to Write a Screenplay

In college, I took a class with John Wilder, a veteran Hollywood film and TV writer, who began the class by writing, “STRUCTURE! STRUCTURE! STRUCTURE!” on the chalkboard.

“What’s the most important part of a screenplay?” he asked at the beginning of nearly every class.

It was obvious what he thought. Not screenplay format. Not the industry standard. Not even main characters.

The most important part of screenwriting is STRUCTURE.

Afterward, I wrote three short screenplays, one of them with a producer of MTV’s Made.

After getting my mind around the strange script writing formatting (which is easiest to master by using a solid screenwriting software), I learned that creating unique stories for film production in such a compressed form is hard.

But it’s been several years since I tried my hand at writing a screenplay. My default is novelist, not screenwriter.

I needed a step-by-step process that would allow me to write a spec script I was proud to share, a good story that was worth a production company’s investment.

“

A good story that is worth a production company’s investment starts first and foremost with a solid structure.

So before I began working on this new project, the one pitched by my lawyer friend, I had to re-familiarize myself with the script writing process.

I needed a plan that uplifted my friend’s pitch with an entertaining plot and STRUCTURE.

Something more than script format alone. (Although, since script format is important when writing a script, I will give you some tips on this at the end of this post.)

I came up with a process for writing a screenplay in five steps.

The 5 Steps to Write a Screenplay

- Craft Your Logline

- Write a Treatment: Your First Sketch

- Structure Your Screenplay’s Outline

- Write a Flash Draft

- Edit

- BONUS: Screenplay Format Must-Haves

Most screenwriters follow these five steps to write a screenplay.

While this doesn’t mean you should follow these steps exactly, hopefully this will be a helpful how to guide as you write a screenplay of your own.

1. Craft Your Logline

A logline is a one-sentence summary of your story, and its primarily used as a marketing tool.

When a studio executive asks you to give him your best pitch, your logline is the first thing you’ll mention. (It also should be used in your elevator pitch.)

Loglines also function as a helpful guide to focus your writing on the most important aspects of your story. In other words, loglines help your story stay on track.

Loglines generally contain three elements:

- A protagonist (main character)

- An antagonist

- A goal

It’s also helpful to put a summarizing adjective in front of your characters to give a sense of their personalities. This, actually, may even be more effective than using a character’s name.

For example, the logline of Star Trek might be:

A headstrong orphan and his Vulcan nemesis must save the Federation (and themselves) from a revenge-seeking Romulan from the future.

Not too hard, right?

(Check out loglines on IMDB for other examples.)

For specific instructions on how to write loglines, visit my post on writing a story’s premise. This post also includes a premise worksheet to help you nail the three elements mentioned above.

2. Write a Treatment: Your First Sketch

Also primarily a marketing document, a treatment gives executives an idea of whether the story is worth their money. However, like the logline, it serves as a helpful tool for the writer, a kind of first sketch of the story.

For most of the history of art, paint was prohibitively expensive, and so before Monet or Picasso would attempt a full-scale painting, they would do a “study,” a sketch of their subject (artists do this today, too, of course).

If a sketch wasn’t coming together, they might save their paint and not make the painting, or else revise the study until it looked worthwhile.

In the same way, a treatment is like a first sketch of a film.

Treatments are generally two- to five-page summaries that break the story into three acts. Here are the three main elements of a treatment:

- Title of the Film

- Logline

- Synopsis

Treatments may include snippets of dialogue and description, but the main focus is on synopsizing the story.

Filmmakers can review a treatment and have a good idea of whether your script is worth investing in (they can probably predict a ballpark range it will cost) and producing.

3. Structure Your Screenplay’s Outline

In this (extremely important) step, you focus on the structure of the story. As Wilder said, in order to master screenwriting, you must master STRUCTURE! STRUCTURE! STRUCTURE!

Your screenplay’s outline is the first step you should completely focus on creating. You likely will never show this to anyone but your writing partners.

Most feature films are from 90-120 pages, and have around forty scenes. These scenes also follow a strict 25-50-25 breakdown, with twenty-five percent given to acts one and three, and fifty percent taking up act two (which can be split into two even parts).

As the screenwriter, your job in the outline is to map out the setting and major events of each scene. You might include major dialogue as well.

The most notable book to understand the structure of a film is Save the Cat by the late Blake Snyder. If you want to learn more about how to write a good screenplay, or even a good story, I highly recommend it.

However, having spent many years in the writing world now, I do think you can take Blake Snyder’s fifteen beats a bit further.

I’ve spent a long time developing The Write Structure to do this, and while writing a feature film has its differences when it comes to certain details, like formatting, structuring stories has core similarities.

Regardless of what structure you choose, remember your screenplay’s outline is primarily for you.

Write as much or as little as you need to.

4. Write a Flash Draft

This is the fun part, your first real draft, and the same guidelines apply here as to your fiction writing:

- Write quickly

- Don’t think too hard

- Don’t edit

Wilder told me his goal was to write the entire first draft of a screenplay, about 120 pages, in three days. If you’ve done the hard work of structuring your story in your outline, this should be easy.

By the way, if you’re not sure how to format your screenplay, don’t forget to read the bonus step below.

Screenwriting software can save you a lot of time with formatting, too. Final Draft is the industry standard, but Scrivener, which is what I use to write books, has helpful screenwriting tools, too.

And others, like Celtx, are free (recommended if you’re getting started, and just want to give writing a spec script a shot).

5. Edit

As with books, I recommend doing at least three drafts.

After you finish your first draft, read it through once without editing (you can take notes though).

In your second draft, focus on major structural changes, including filling gaping holes, deepening characters, removing characters who don’t move the story forward, and even rewriting entire scenes from scratch.

In your third draft, focus on polishing: specifically, on making your dialogue pop. If this is your final draft, don’t forget to add a title page and double check all other screenwriting formatting musts.

Once your script is complete, it’s time to get feedback and begin sending it to studios. Keep in mind, most production companies don’t take unsolicited scripts, and if this is the case, you’ll need an agent.

P.S. If you want to hire a developmental editor to review your story’s structure and make it the best draft it can be, check our certified Story Grid Editors.

Good luck!

BONUS: Screenplay Format Must Haves

If you’ve never written a screenplay before, you might feel overwhelmed by a screenplay’s format. Keep in mind that if you purchase a screenwriting software like Final Draft, the software will take care of most of the particular requirements, like page margins (like the left margin, which is 1.5″).

But, because screenwriters should understand screenplay formatting and when to use certain formatting musts, here’s a list of formatting basics to keep in mind as you write your first draft:

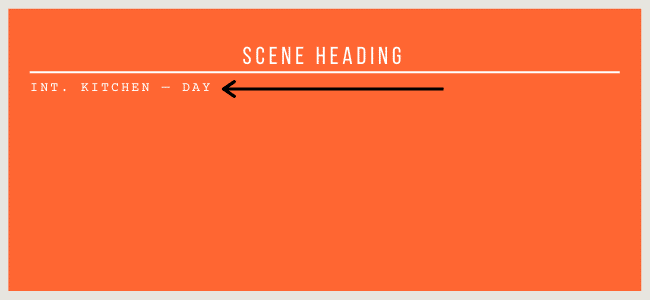

Scene Heading

A scene heading, or slug line, indicates where the action in the new scene is happening. This line is in ALL CAPS.

In the line, you’ll see INT. (interior) or EXT. (exterior) and the location for the scene, followed by a dash and then the time of day.

Slug lines mark the start of a new scene, and help the reader keep a sense of movement between locations.

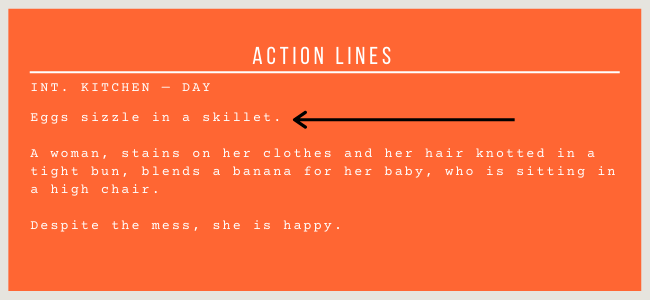

Action Lines

Action lines go beneath the scene heading. They are as descriptive as possible but short, focusing on the action occurring and visuals.

Action lines, unlike description used in books, will often be more direct than five sense writing, which aims to create an emotional response in readers of novels.

There will rarely (if ever) be more action lines in a screenplay than dialogue.

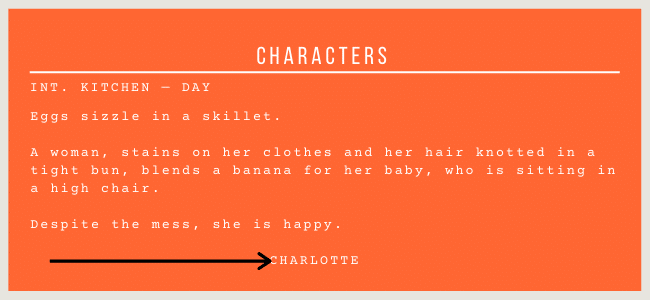

Characters

Character names appear above the dialogue and are always in ALL CAPS. Every time a different character speaks, we will see a new name above the dialogue.

In some cases, action breaks up dialogue, but the same character is speaking. These will be marked with an extension that indicates the same character is continuing to talk (see extensions below).

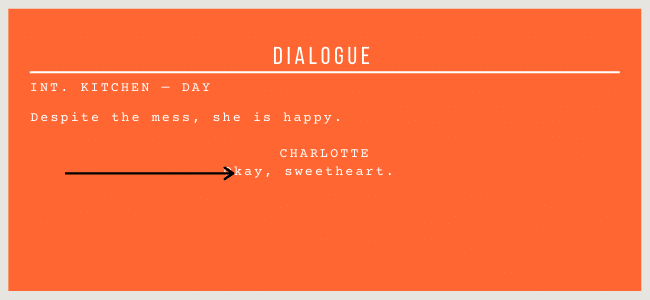

Dialogue

Dialogue is the most important part of a screenplay. It is the majority of a what’s written in a script, and gives filmmakers and actors direction about how the story is told.

Aaron Sorkin (Oscar winner for The Social Network among other films and TV hitmakers like The West Wing) is a beloved screenwriter in Hollywood, most notably known for his mastery of dialogue.

If you’re hoping to learn how to master dialogue like Sorkin, you might consider checking out Aaron Sorkin’s MasterClass. You can read our full review of his MasterClass here.

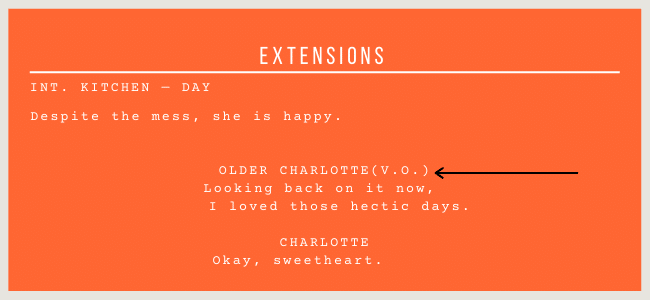

Extensions

Extensions tell the reader how dialogue is heard. These go next to the character name in parentheses.

This is formatting that most screenwriting software takes care of when you use it.

Some cases where you would use an extension include:

- Voice Over (V.O.): when we hear a narrator who isn’t on screen, and the characters on screen also do not hear the narrator (minus some exceptions used for comedic effect, like George of the Jungle)

- Off Screen (O.S.): when the character speaking is heard by the other characters on screen but is not on screen themselves, like an announcement made over an intercom

- Into Devices: when a character is speaking into a device, like a phone

- Pre-Lap: when dialogue started at the end of one page extends onto the next page

- Continued (CONT’D): when the same character is speaking as the previous line of dialogue broken up by action

Like characters, all extensions are in ALL CAPS.

Extensions are also technical directions, indicating where the actor saying the line is, versus . . .

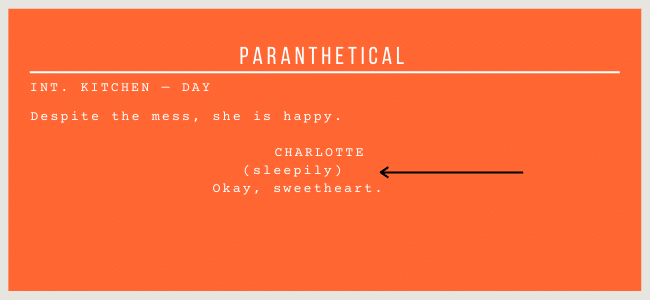

Parentheticals

A parenthetical is written like an extension (in parentheses beneath the character name), but instead explains how a line should be performed.

Sarcastically, for example. Or Laughing.

Or, beat written in lower case, which indicates a pause.

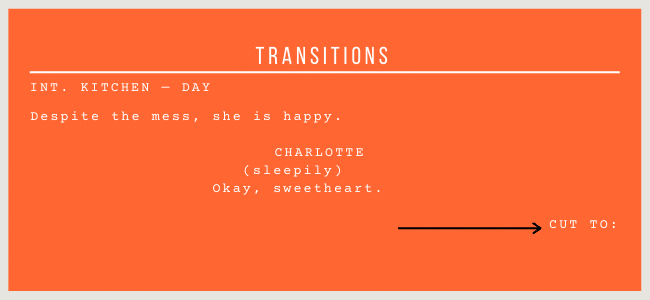

Transitions

Transitions tell an editor how they should edit a scene. This is when you’ll see something like CUT TO: on the right side of the page.

Sometimes Used: Camera Shots

Keep in mind, while you’ll see camera shots in finalized scripts, screenwriters don’t always include this in their spec script.

This is because shot choices belong to the director, and they will very likely change what’s written.

If You Sell Your Script, Watch as It Gets Torn Apart

The film industry is collaborative.

For most films, multiple screenwriters work on a script, and then, in the production process, the script constantly changes because of feedback from producers, actors, and the director.

It’s not easy being a screenwriter in Hollywood. Often, the first writer on a screenplay won’t even get credit because so much of the original screenplay has been revised.

Others might sell a script for six digits, but then constantly worry about not being able to sell the next one.

This is something I’ve been thinking about as I work on my new project.

Even if our film is lucky enough to get bought, my chances of having my name on the film as a first-time screenwriter and industry outsider are still quite small. (I’d also want to make sure that I’m part of the Screenwriters Guild.)

Fortunately, I learned this last lesson from John Wilder:

“That’s why structure is so important. They can completely rewrite the dialogue, the action, and the setting descriptions, but if you have a solid structure, you’ll still see your name at the end of the film.”

Wouldn’t that be a treat?

FADE OUT:

Have you ever written a screenplay? What is your process? Let me know in the comments.

Want to take your screenplay skills to the next level? We love Aaron Sorkin’s MasterClass on Screenwriting. Check out our full review here. Or, head straight to the MasterClass to take a look and step inside!

Explore Aaron Sorkin’s MasterClass

Note: Some of the links above are affiliate links. We only recommend books and tools we’ve used and found helpful, and by purchasing them, you help support this writing community. Thanks!

PRACTICE

Write a logline, either for your work in progress or for a new story. Remember, your logline should include:

- A protagonist (main character)

- An antagonist

- A goal

Take fifteen minutes to write. When you’re finished, post your logline in the comments section.

And if you post, make sure to comment on a few loglines by other writers. Let them know whether you’d like to see their film or not!

Enter your practice here: