Rising Motion: Definition and Examples of This Dramatic Construction Component

Have you ever wondered why rising action is so important in storytelling? Why building conflict and characters matter? Why you can’t get to the point of the story too quickly?

Note: This article contains an excerpt from my #1 best-selling book, The Write Structure, which is about the hidden structures behind bestselling and award-winning stories. If you want to learn more about how to write a great story, you can get the book for a limited-time low price. Click here to get The Write Structure ($5.99).

If you’ve ever told a good story—one that has your friends or family on the floor laughing, or else on the edge of their seat asking, “What happened next?!”—then you know it’s important to draw out a reader’s interest.

You can do this by crafting Rising Action in your plot, and it’s essential to get this right if you want to write entertaining, informative, and deeply connecting stories.

In this article, I’m going to talk about the literary term rising action: what it is, how it works in a story, how it’s been treated by scholars who study story structure throughout history, and finally how you can use it to write a great story.

Let’s jump in!

Rising Action Definition

The rising action in a story moves the plot toward the climax through a series of progressively more complicated events and decisions by the main character or characters, leading up to a final decision of great significance.

As an element of story structure, it is one of the six major elements of plot, occurring after the exposition and building toward the climax. Some plot structure methodologies call it the rising movement or progressive complications.

As the source of the main conflict, it contains most of the action in a story, and is usually the longest piece.

Dramatic Structure

Before we talk about how to use the rising action in your writing, let’s talk about dramatic structure or narrative structure in general.

Dramatic structure is an idea, originating in Aristotle’s Poetics, that effective stories can be broken down into elements. At The Write Practice, we define six elements of dramatic structure:

- Exposition

- Inciting Incident

- Rising Action/Progressive Complications

- Dilemma/Crisis

- Climax

- Denouement

When writers are constructing a story they should include these six elements.

Rising action is the longest part of the story, and one of the most important parts of dramatic structure because it contains most of the decisive action in a story.

If the exposition and inciting incidents are the beginning of the story and the climax of the story is the end, the rising action makes up the middle of the storyline.

Note: You might be expecting to see falling action in this list. At The Write Practice, we don’t consider falling action a plot element. If you’re interested in learning why, check out our article on falling action here.

How the Rising Action Works in a Story

The purpose of the rising action is to lead the character to make a difficult decision.

However, most people, including most characters, are reluctant to make decisions, especially difficult decisions.

That’s what the rising action is for, moving the characters to a point where they are forced to make a decision.

The way it does this is by putting the characters through a series of progressively more complicated events and choices.

In fact, Story Grid, a dramatic framework formulated by Shawn Coyne, calls the rising action “progressive complications.” Things get more and more complicated for the protagonist until they reach a turning point and they’re forced to make a decision. That point of decision-making is a crisis for the character.

And this crisis is always a choice between two conflicting values, whether safety or sacrifice, love or duty, performance or righteousness.

The Rising Action Builds the Conflict Between Two Values

This, by the way, is where drama comes from: from the conflict between these two values and the protagonist’s final choice.

You’ve heard that stories need conflict, that conflict is what drives the plot (both external conflict and internal conflict). But effective stories are not driven by conflict for the sake of conflict, but conflict for the sake of choice.

In other words, it is the character’s decisions that drive effective stories forward, not just the events that the character is experiencing.

Practically speaking, how does that work?

In a moment, we’ll look at several different examples. But first, I need to make one quick note about the different ways people talk about the rising action.

“

Stories aren’t made of events that happen, but of choices characters make. The purpose of rising action is to lead your character to the point where they have to make a difficult decision.

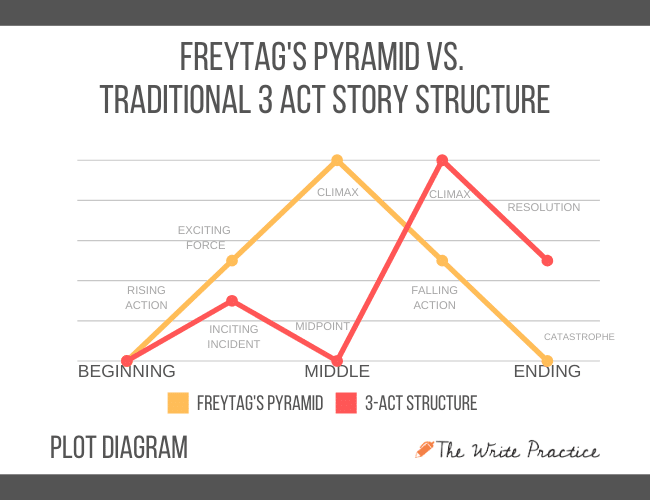

Freytag’s Rising Action vs. Modern 3-Act Story Structure

Freytag’s Pyramid is one of the most common frameworks for story structure. Formulated by Gustav Freytag in 1863, this concept, more than anything else, has shaped the way people think about story structure today.

That being said, Freytag’s own understanding of plot and structure differs greatly from how most writers think and talk about it now.

Writers today include all the same elements as Freytag. But we put them in different places, as you’ll see in the illustration below.

While this illustration isn’t perfectly to scale, if the rising action contains everything after the exposition and through to the climax, then as you can see, in Freytag’s model, the rising action—which Freytag calls the rising movement—is significantly shorter than in a modern three-act story structure model.

Despite their differences, these models can overlap, and you can use both to better think through the structure of your story. I mention this mainly to clarify the language I use in the examples below.

Examples of Rising Action

Now let’s look at examples of the rising action, rising movement, or progressive complications in action.

As we analyze them, let’s begin with the choice each story builds toward. As I said above, the purpose of the rising action is to force a character into a choice because choices are the source of drama.

Thus, we will work backward from that decision, showing how the rising action forces that character into that decision.

Rising Action in Romeo and Juliet

Beginning with the crisis, how does the rising action in Romeo and Juliet work?

The climactic choice/crisis: End their lives OR stay alive in a world without the other.

Out of context, both of those decisions are crazy. Why would a young, newlywed couple decide to separate? Even more extreme, why would two young people with so much potential from good families decide to end their lives?

These decisions are the core of the story, the climactic moments. They are also decisions no one would come to without some good reason.

The rising action provides the reason. If we begin from that choice and work backward, we can see how the rising action builds to that crisis.

The events in the rising action are:

- Romeo believes Juliet is dead.

- Juliet fakes her own death, but the message telling Romeo of her plan is never delivered.

- Juliet is forced to become engaged to another man (even though she’s already married to Romeo).

- Romeo is exiled, and he and Juliet part tearfully.

- Romeo kills Tybalt, Juliet’s cousin, after Tybalt kills Mercutio, Romeo’s best friend.*

- Romeo and Juliet elope in secret.

- Romeo and Juliet meet at a party and fall in love, despite the fact that their families are enemies.

- Exposition: Two rival families fight in the streets of Verona.

*This is where Freytag marks the end of the rising movement, with the climax being Romeo and Juliet parting tearfully. Most modern three-act story structures would mark that scene as part of the rising action/progressive complications.

From this perspective, the choice makes perfect sense, and the stakes are well set up so that this choice is significantly difficult enough.

Climactic choices must be difficult. If they’re not, the writer hasn’t done their job right.

Also note, the rising action covers a lot of ground, a large majority of the story. Even if you end the rising action where Freytag does—and again, few writers today would do that—it still covers almost half of the play.

Let’s look at another example, this one from Ready Player One:

Rising Action in Ready Player One

What is the crisis, the climactic choice that Wade Watts, A.K.A. Parzival, has to make in Ready Player One?

First, a brief summary, in case you’re not familiar with the story. In a dystopian future, Wade Watts spends most of his time in a virtual reality world called the OASIS. Halliday, the rich and famous creator of the OASIS, has died, and he’s left an elaborate puzzle hidden in this virtual world to determine who will inherit his fortune and control of the OASIS. Wade stumbles upon the first clue, then races thousands of other hopeful puzzle-solvers to win the game.

The climactic choice/crisis: Go it alone and win the prize, OR accept help and share the winnings from the game with his friends?

The winnings, in Ready Player One, include billions of dollars, plus full administrative control of the OASIS. It’s everything Wade Watts has ever wanted. Why on earth would he even be tempted to share that?

The rising action gives us the answer. As with Romeo and Juliet, if we begin from that choice and work backward, we can see how the rising action builds to that crisis.

The events in the rising action of Ready Player One include most of the events in the story, from (spoiler alert!) the moment he shares the information about how to beat Joust and receive the first key with Art3mis up until (more spoilers) he hesitates before entering the final crystal gate and getting the chance to play to win Halliday’s Easter egg.

Building up to that moment, Wade undergoes a personal transformation. He changes from someone who chooses, on principle, to do things alone to someone who has a few close friends—including a psuedo-girlfriend in Art3mis. Then he becomes someone who is once again alone and alienated from everyone he cares about, before ultimately becoming someone who is willing to risk it all and sacrifice for the sake of his friends.

As he goes through this maturation process, he learns the story of Halliday, a tragic model of someone who decided to alienate his friends for the sake of his creation, the OASIS.

Through the rising action, in other words, the choice becomes whether Wade will become like Halliday, his hero, or learn critical lessons from Halliday and share power with his friends.

Can You Describe the Rising Action in This Scene From Friends?

Now that you’ve seen two examples, and before we get to our last example, try finding the rising action yourself in this clip from the hit TV show Friends.

And make sure to check your answers at the end of this post!

Rising Action in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone

The rising action is long, containing most of the story. I also like the term progressive complications for this section of the plot, because the rising action is not one thing, but many things which are all growing more and more complicated over time.

Let’s take a quick look at Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone to see how much of the story it can take up:

- Exposition: In a world with magic, a baby boy has mysteriously overcome Voldemort, the most powerful wizard in the world, losing his parents in the process. Professor Dumbledore leaves the baby, Harry Potter, at his uncle and aunt’s house to be raised, where throughout his childhood, he is bullied by his relatives, including his cousin Dudley.

- Inciting Incident: Upon turning eleven, Harry Potter begins receiving letters from an unknown source inviting him to join a boarding school for wizards called Hogwarts.

- Rising Action/Progressive Complications: Harry and the Dursleys flee to a deserted island to escape the letters. Hagrid finds them and delivers the letter, leaving with Harry the next morning so he can attend the school. They shop for school supplies in Diagon Alley. On the way to school he meets new friends and makes enemies. When he arrives at Hogwarts, he is sorted into Gryffindor. He begins taking classes and orients himself to magic and Hogwarts life. He faces off against a troll. Other adventures happen, including Christmas, and the discovery that Voldemort is hunting a powerful stone that grants its owner immortality. Harry joins the quidditch team and is almost killed during a match, they think by Professor Snape, who they believe is out to get the stone for Voldemort. More shenanigans as they track down the stone.

- Dilemma: Break into the secret hiding labyrinth protecting the sorcerer’s stone and risk explosion or even death OR do nothing but risk Voldemort returning when he captures the stone.

- Climax: Harry and his friends make their way through the labyrinth and face off against Voldemort and his accomplice.

- Denouement: Harry and his friends survive and are honored in front of the whole school.

As you can see, the rising action contains most of the story.

The Rising Action Belongs in Each Act and Each Scene, Too

Your story needs rising action, but so does every act and even every scene.

That means in the average novel, film, or screenplay—which has fifty to seventy scenes—you should have fifty to seventy rising action moments and fifty to seventy climactic choices.

Why so many?

Because this is the heart of drama: complications creating conflict between values resulting in a choice. If you don’t have progressively more difficult complications and if you don’t have progressively more significant choices, you don’t have a story.

So figure out the choices your characters need to make, and then build to them using the rising action.

Key Ideas About the Rising Action

- The rising action moves the plot toward the climax. It does this by building the action with a series of progressive complications, or events that create conflict by preventing a character from easily attaining their scene or story want/goal.

- As the source of the chief conflict, the rising action contains most of the action in a story, and is usually the longest piece.

- The purpose of the rising action is to lead the character to make a difficult decision.

- Effective stories are not driven by conflict for the sake of conflict, but driven by conflict for the sake of forcing a choice. The choice should be between two values.

- Your story and every scene in it needs rising action.

Rising Action in the Scene Where Ross Finds Out Rachel Likes Him in Friends

Did you see the rising action in the episode where Ross finds out Rachel likes him? Here’s what I see:

- Exposition: Ross comes over to the apartment. Rachel is alone and hungover.

- Inciting Incident: Ross asks about Rachel’s date.

- Rising Action/Progressive Complications: Ross and Rachel chat about Rachel’s poor date. Rachel can’t quite put her finger on a conversation she thinks she had with Ross. Ross asks Rachel if he can check his messages. Rachel remembers calling Ross the previous night.

- Dilemma: Confess to Ross about liking him OR pretend like the message isn’t a big deal.

- Climax: Rachel (embarrassed) and Ross (shocked) go back and forth on when they liked one another. Ross doesn’t know what to make of this since he’s with Julie now.

- Denouement: Ross leaves to get a cat with Julie, but he’s frazzled. Rachel is left alone and disappointed.

What is an example of rising action in a film or novel that you particularly like? Let us know in the comments.

PRACTICE

Let’s put the concept of rising action to use with a creative writing exercise. Here’s what I want you to do:

List five possible complications based on the following climactic choice:

Love OR money

After listing your complications using that choice, use one of them as a creative writing prompt to write a new scene.

For instance, I might write this for a complication: “A rich woman falls in love with a poor man.” Then I might write a scene in which she’s torn between her status and her love.

What other complications can you imagine? What scene will you choose to write?

Write for fifteen minutes. When your time is up, post your practice in the practice box below. And if you post, be sure to give feedback to at least three other writers.

Happy writing!

Enter your practice here: