Factors of a Story: 6 Key Plot Factors That Each Story Wants

One thing writers have told me consistently is that knowing story structure and the major plot points—or points of a story—makes writing great stories easier. But what are the main points of a story? How can you get them into your books?

I’ve personally found story structure to be incredibly helpful, not just in writing novels and screenplays, but also in memoir and even, sometimes, writing nonfiction books.

In this guide, we’re going to talk about the basic points of a story and how to use story structure to make your writing easier and more effective. I’ll share the six major plot points and talk about a few other points you might look for when writing a book that will give you a general roadmap to writing your story.

We’ll also look at a couple of examples so you can see how these plot points in action. And then I’ll give you a writing exercise to put your new knowledge into action.

To do this, let’s first talk about what plot even is, and how it might help you with your writing and screenwriting.

Note: This article contains an excerpt from my new book The Write Structure, which is about the hidden structures behind bestselling and award-winning stories. If you want to learn more about how to write a great story, you can get the book for a limited time low price. Click here to get The Write Structure ($5.99).

What is a Basic Plot?

Plot is a sequence of events in a story in which the main character is put into a challenging situation that forces them to make increasingly difficult choices, driving the story toward a climactic event and resolution.

In other words, plot is the events that make up your story. Which means plot points are the big moments, the key events that change everything.

“

Plot points are the big moments in a story that change everything. There are six main plot points in every story. Learn about them in this article!

What’s interesting is that as stories have evolved over thousands of years, people have begun to see patterns in those events.

The Greek philosopher Aristotle was the first recorded person to talk about the patterns stories make, but others have come up with entire frameworks for plot structure, including ancients like Horace to modern authors like Gustav Freytag to contemporary theorists like Robert McKee and Shawn Coyne.

Story structure describes those frameworks for understanding how stories are made. This includes important elements like the subjects, characters, and major plot points.

That’s why story structure can be so helpful, because it gives you a way to think about story that can help you come up with ideas when you’ve run out. They can help you choose between the different directions your story might go. And they can help you evaluate what’s working in your story, and what’s not.

One popular form of this is called three act structure, first suggested by Aristotle himself, which divides a story into three separate parts.

Three act structure is best described by this 100 year old writing advice:

“In the first act, put your character up a tree. In the second act, throw rocks at them. In the third act, bring them down.”

We don’t have time to go through all story structure theory in this article, but we’ll cover the major plot points and look at some examples.

If you want to go deeper, check out my book The Write Structure, which fully explores the principles behind what makes best-selling stories work and teaches you to write them.

You can find The Write Structure and get a copy here.

The 6 Basic Plot Points

To start our conversation about plot points, you need to know that there are six basic plot points. These are more than just plot points, though. They are the six elements of plot found in every story.

Originally developed by Gustav Freytag, over the years they’ve expanded and evolved into the six that we teach in The Write Structure.

“

Knowing the six plot points of a story can help you figure out the direction your story could take—and it can help you evaluate what’s working (or not) in your story.

Plot Point 1: Exposition

The exposition is a scene or set of scenes that introduce the audience to the characters, world, and tone of the story.

The exposition is a point at the beginning of a story where nothing really happens, you’re just setting up the events, the world, and the characters.

Focus here on characterization, setting description, and developing the problems that will begin shortly.

For more on the exposition, see our complete guide here.

Plot Point 2: Inciting Incident

The inciting incident is the event in a story that upsets the character’s status quo and begins the story’s movement. It sets the story in motion.

In other words, the inciting incident is a problem that forces the characters into action, and as such, it’s the story’s first major turning point.

For an event to qualify as an inciting incident, it must meet five criteria:

- Early. A story’s inciting incident occurs early in the story, sometimes in the first scene, almost always within the first three to four scenes.

- Interruption. Inciting incidents are an interruption in the main character’s normal life.

- Out of the protagonist’s control. Inciting incidents are not caused by the character and are not a result of the character’s desires.

- Life-changing. The event must have higher-than-normal stakes and the potential to change the protagonist’s life.

- Urgent. Inciting incidents necessitate an urgent response.

When you’re thinking about the inciting incident, the big problem that starts the plot of your story, make sure it meets the criteria above.

For more on the inciting incident, see our complete guide here.

Plot Point 3: Rising Action/Progressive Complications

The rising action in a story moves the plot forward through a series of progressively more complicated events and decisions by the main character or characters, leading up to a final decision of great significance, the dilemma (next plot point).

Most characters, like most people, are reluctant to make decisions, especially difficult decisions. That’s what the rising action is for, moving the characters to a point where they are forced to make a decision.

The way it does this is by putting the characters through a series of progressively more complicated events and choices. All of which build up to a moment where the protagonist must make a decision, regardless of the consequences that come with it.

For more on the rising action, see our guide here.

Plot Point 4: Dilemma

A dilemma is the point when a character is faced with an impossible choice. This choice must be between either two good or bad things.

This is also the most important plot point in a story. It’s a pivotal moment that forces the character to take action, and those actions come with consequences—even if they decide not to act.

Great stories are built around a single, overarching choice. The entire story builds to this dilemma. And the denouement, the story’s resolution, falls away from this dilemma. The climax, the highest point of action in the story, emerges directly from the dilemma.

Which is all to say: if you don’t have a dilemma, you don’t have a story.

For more on the dilemma. see our guide here.

Plot Point 5: Climax

The climax is the point where the protagonist makes their choice. It is the moment of highest drama, action, and movement.

The climax is usually very close to the end of a story, often the second to last or third to last scene (although sometimes longer denouements are required, leaving the climax further from the end).

Some stories also have the story’s chief climax at the end of the second act, not the third. In these cases there may be a smaller climax near the end of the story.

For more on the climax. see our complete guide here.

Plot Point 6: Denouement

The denouement is the final part of a narrative, usually in which the outcome of the story is revealed.

It’s the moment we learn what the world looks like after going through all the drama of the story.

After the climax, most stories wrap up quite quickly, within one or two scenes.

That means that the denouement, as the final part of a story, is generally one or two scenes long.

For more on the denouement, see our guide here.

Plot Points Are Specific to Genre and Plot Type

Every story that works has the above basic plot points, so knowing them can be very helpful. However, depending on your plot type, how these plot points look in your story might look very different depending on your plot type and genre.

“

Every story has six key points in a story. However, depending on your story’s genre, these plot points might look different.

For example, the inciting incident of a Hallmark Christmas love story is the “meet cute,” the moment where the couple first meet, usually in an awkward and funny way. The meet cute inciting incident universal in all love story plot types.

However, the inciting incident in a revenge, action plot like the classic novel The Count of Monte Cristo or the film John Wick is when some great crime is committed against the main character, a crime which, of course, requires retribution.

How do you know what plot points your story needs? You must study the stories of your plot type and genre. Writers read, and if you want to understand how to tell a great story, you need to know the great stories that have been written before you.

At the same time, we’ve made it easier for you by compiling a plot type guide with some of the most common plot points specific to each type.

You can check it out, and find the plot points specific to your type of story, here.

Also note that different forms handle plot points differently. For example, short stories will have the six basic plot points above, but just in a condensed format. They also may not include other plot points specific to the genre.

In the same way, sitcoms usually have two plots, an A plot and a B subplot, and contain very specific plot points for each. These points adhere to the basic plot points above, but they have their own, genre-specific names and feel. Here’s an excerpt from The Write Structure on how they look:

• Teaser (exposition)—one to three minutes

• Trouble: Story A (inciting incident)—minute three

• Trouble: Story B (inciting incident)—minute six

• The Muddle: Story A (rising action, dilemma)—minute nine

• The Muddle: Story B (rising action, dilemma)—minute twelve

• The Triumph/Failure: Story A (climax)—minute thirteen

• The Triumph/Failure: Story B (climax)—minute fifteen

• The Kicker: Story A + B (denouement)—minute nineteen

As you can see, all the basic plot points are present, but they’re worked into the genre and form’s own unique structure.

Other Plot Points

Apart from the basic six plot points, and their iterations through each act, there are a few other plot points you might find helpful as you’re mapping out your story.

1. Point of No Return

The point of no return plot point occurs directly after the act one dilemma and climax. It is when the character realizes that the choice they made at the end of act one has such major consequences that they can’t go back to the status quo and how things were previously.

After a protagonist makes this decision, the story moves from act one to the second act.

In other words, the protagonist crosses the first threshold and begins the main journey of their story.

2. Midpoint (or Mirror Moment)

The midpoint, according to story structure theorists like James Scott Bell, occurs somewhere in the middle of the story (the exact middle, according to some). It is when your character realizes that something has changed about their approach to solving the problems posed by the inciting incident and rising action, whether it’s a personal transformation or transformation in their tactics.

This midpoint transformation could be caused by them reframing how they view their situation, realizing the situation was never what they thought in the first place, or choosing to go about addressing the situation in a completely different way.

Often the midpoint is considered either a false triumph (meaning things are soon going to get much worse) or a false failure (meaning things are soon going to get much better).

In this moment, the protagonist also starts to become active in their actions. In other words, from this moment on, they start to initiate action, which will build up to the climax of their story.

Note: Freytag called the midpoint the climax, and he believed it was the most important scene in the whole story. While we would now say the climax occurs much later in the story, he was the first to theorize that most stories had two halves that mirror each other.

3. Dark Night of the Soul

The dark night of the soul plot point usually occurs at the end of act two. The character has attempted to solve their problems, but they have failed and reached a breaking point during which they question their ability to solve the problem at all.

During the dark night of the soul, they reach their lowest moment, which sets the plot up perfectly for a major realization about how they can finally solve their problem, pushing us into act three and setting up the climax and denouement of the story.

4. The Hero’s Journey: The 12 Plot Points

Hero’s Journey is a story telling framework first theorized by Joseph Campbell and then codified and translated for writers by Christopher Vogler.

While we don’t have time to fully explore the Hero’s Journey archetype in this guide, we do have an excellent resource on the full twelve-step framework.

Check out the full twelve-step Hero’s Journey guide here.

How to Expand Your Novel Outline

Whether you’re a planner or a pantser, if you’re working on their first draft, I think it’s helpful to have a loose outline of the six plot points above. Even if you hate the idea of them, a simple six sentence outline can save you when you get lost in your draft (and I say “when” not “if” because everyone gets lost in the first draft at some point).

However, if you’re looking for an outline that’s a little more extensive so that you feel more prepared for the writing process, you can expand your six sentence outline.

That’s because while every story that works has the six plot elements above, also every act has them as well.

That means in the three-act structure, there are actually eighteen plot points that you can explore in your story.

Here’s how it looks:

Act 1:

- Exposition 1

- Inciting Incident 1

- Rising Action 1

- Dilemma 1

- Climax 1

- Denouement 1 (Point of No Return is here, if you have one)

Act 2:

- Exposition 2

- Inciting Incident 2

- Rising Action 2 (Midpoint will go here, if you have one))

- Dilemma 2

- Climax 2

- Denouement 2 (Dark Night of the Soul is here, if you have one)

Act 3:

- Exposition 1

- Inciting Incident 3

- Rising Action 3

- Dilemma 3

- Climax 3

- Denouement 3

Some writers, notably Steven Pressfield, call this structure a foolscap, because it’s your entire story on a single piece of paper.

This eighteen sentence outline is the process we walk every writer through in The Write Structure. We also have a beautiful, easy to use plot template you can get in The Write Plan planner, our step-by-step book planner. Check out the planner here.

Plot Points That I Don’t Recommend Using

There are some plot points you might have heard of that I don’t recommend applying to your writing, either because they’re overly confusing, arbitrary, or present in only certain types of stories.

Pinch Points

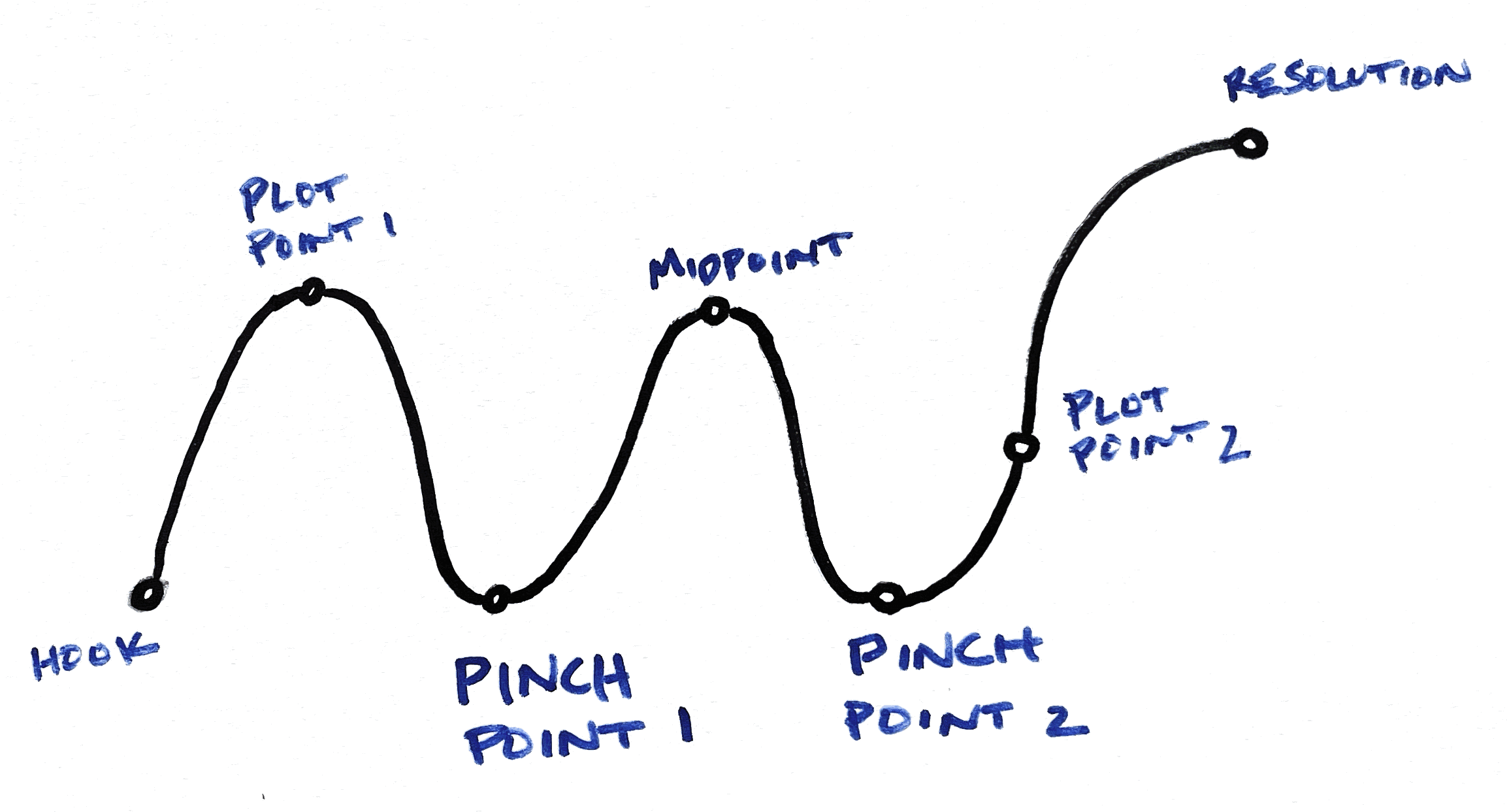

While there are several plot frameworks that use pinch points, the seven-point plot structure, seen below, is the most well known.

A pinch point, in this framework, is a turning point in which the character reaches a low, usually because they’ve been (temporarily) defeated by the antagonist. According to the seven-point plot structure, there are always two pinch points, with the first pinch point occurring either at the beginning of the second act or the end of act one, depending on who you talk to, and the second pinch point occurring at the end of act two.

What’s good about this idea is that every story must explore major highs and major lows, the full range of the value scale your story is about. If you don’t fully explore the lows, the highs won’t be as meaningful.

However, stories come in many different arcs. In fact, a team of researchers from the University of Vermont found that there are six major story arcs that stories take, and the diagram above is only one of them (called the Cinderella Arc).

While two pinch points certainly occur in some story arcs, they don’t occur in every arc.

Check out our complete story arcs guide here and see if you can spot where the pinch points might occur.

Also, personally I find the term confusing. Pinch points? Like the protagonist is getting pinched by the antagonist? Weird.

P.S. Dark Night of the Soul is synonymous with pinch point #2.

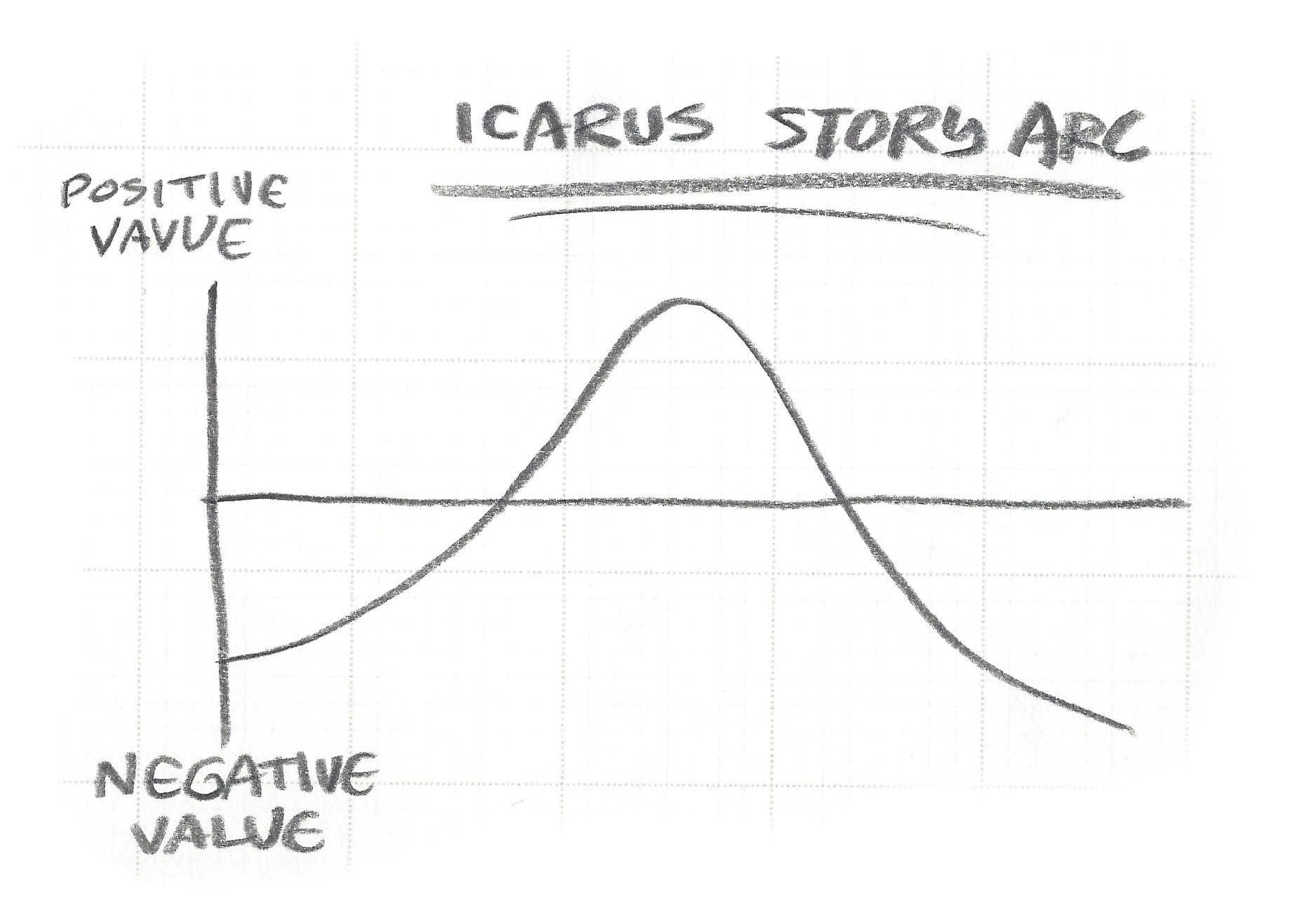

Falling Action

The falling action is one of Freytag’s major plot points. It occurs just after the midpoint (what he called the climax) and its purpose is to wind down the story down from the climax to the resolution and the story’s end.

The problem is that, like pinch points, not all arcs have them. See, Freytag was primarily interested in the Icarus arc, see below.

He was interested in tragedies, and he didn’t really believe in stories with happy endings. Yes, they existed, but were they good? To Gustav Freytag, the answer was no, they were not.

And so his understanding of plot centered around this single arc, and the terms he used, like falling action, reflect that. However, many stories don’t have a falling action, they occur in different places than Freytag said, or they have several falling actions. And that’s okay.

Great even.

All that’s to say, if someone tells you your story needs to have a falling action, politely say thank you for the feedback and move on. It’s popular advice that doesn’t reflect many stories.

For more on the falling action (and why it doesn’t exist) check out this article.

Examples of Plot Points in Great Stories

To better understand how plot points work, let’s break down two popular stories.

Star Wars: A New Hope (Episode IV)

Let’s break Star Wars: A New Hope down into a six sentence outline based on our six basic plot points.

1. Exposition: There’s a galactic civil war and Princess Leia sends a distress message on two droids to someone called Obi-wan Kenobi. On a remote desert planet called Tatooine, a young man named Luke Skywalker wants to join the rebellion to become a star fighter pilot.

2. Inciting Incident: Luke sees part of the distress message hidden on his newly acquired droid, R2D2.

3. Rising Action/Progressive Complications: Everthing from when Obi-wan saves Luke and invites him to learn about the force and confront the Empire to the battle at the Death Star. (Note: in an 18 sentence outline, this section will get much more fleshed out.)

3B. Midpoint: Tarkin orders Princess Leia’s death and the Millennium Falcon discovers Alderon has been destroyed and is sucked by the Death Star tractor beam.

4. Dilemma: Trust the force and risk missing the target while also looking like a fool or rely on technology and risk failing again.

5. Climax: Luke trusts the force and fires the torpedo that destroys the Death Star.

6. Denouement: Luke and Han Solo are rewarded for saving the rebellion/galaxy.

Know the 6 Points of a Story

Knowing the six plot points—or points of a story—for your story can help you build tension and figure out what’s working or not in your plot.

However, how these plot points are applied depends on the genre you are writing.

By studying stories, you will start to recognize how these plot points occur more and more. And when you’re stuck, bookmark this article. Refer back to it, and then use the information to help plot out your next story!

How about you? Do you like to figure out the plot points in your story before you write? Or do you prefer to just write and let the plot points work themselves out. Let us know in the comments.

PRACTICE

Let’s practice using plot points by breaking down another well-known story, this time Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone.

Take fifteen minutes and break down Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone into a six plot point outline using the plot points above.

When you’re finished, post your outline in the Pro Practice Workshop here.

And after you post, be sure to give feedback to at least three other writers.

Happy plotting!