Level of View in 2023: Third Particular person Omniscient vs. Third Particular person Restricted vs. First Particular person

In my experience as an editor, point of view problems are among the top mistakes I see new writers make, and they instantly erode credibility and reader trust. Point of view isn’t easy though, since there are so many to choose from: first person, third person limited, third person omniscient, and second person.

What do those even mean? And how do you choose the right one for your story?

All stories are written from a point of view. However, when point of view goes wrong—and believe me, it goes wrong often—you threaten whatever trust you have with your reader. You also fracture their suspension of disbelief.

However, point of view is simple to master if you use common sense.

This post will define point of view, go over each of the major POVs, explain a few of the POV rules, and then point out the major pitfalls writers make when dealing with that point of view.

Need help with point of view? To get a cheatsheet of the two most common POVs used in fiction, click here.

Need help with point of view? To get a cheatsheet of the two most common POVs used in fiction, click here.

Point of View Definition

The point of view, or POV, in a story is the narrator’s position in the description of events, and comes from the Latin word, punctum visus, which literally means point sight. The point of view is where a writer points the sight of the reader.

Note that point of view also has a second definition.

In a discussion, an argument, or nonfiction writing, a point of view is an opinion about a subject. This is not the type of point of view we’re going to focus on in this article (although it is helpful for nonfiction writers, and for more information, I recommend checking out Wikipedia’s neutral point of view policy).

I especially like the German word for POV, which is Gesichtspunkt, translated “face point,” or where your face is pointed. Isn’t that a good visual for what’s involved in point of view? It’s the limited perspective of what you show your reader.

Note too that point of view is sometimes called narrative mode or narrative perspective.

Why Point of View Is So Important

Why does point of view matter so much?

Because point of view filters everything in your story. Everything in your story must come from a point of view.

Which means if you get it wrong, your entire story is damaged.

For example, I’ve personally read and judged thousands of stories for literary contests, and I’ve found point of view mistakes in about twenty percent of them. Many of these stories would have placed much higher if only the writers hadn’t made the mistakes we’re going to talk about soon.

The worst part is these mistakes are easily avoidable if you’re aware of them. But before we get into the common point of view mistakes, let’s go over each of the four types of narrative perspective.

The Four Types of Point of View

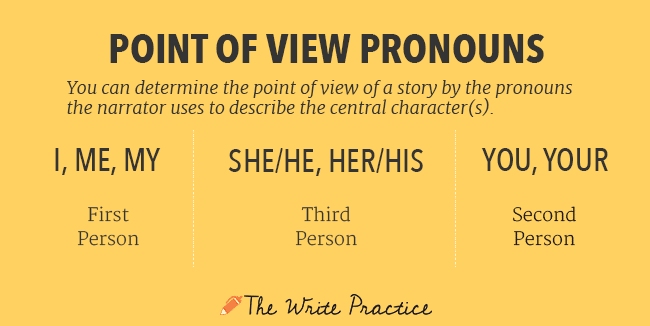

Here are the four primary types of narration in fiction:

- First person point of view. First person perspective is when “I” am telling the story. The character is in the story, relating his or her experiences directly.

- Second person point of view. The story is told to “you.” This POV is not common in fiction, but it’s still good to know (it is common in nonfiction).

- Third person point of view, limited. The story is about “he” or “she.” This is the most common point of view in commercial fiction. The narrator is outside of the story and relating the experiences of a character.

- Third person point of view, omniscient. The story is still about “he” or “she,” but the narrator has full access to the thoughts and experiences of all characters in the story. This is a much broader perspective.

I know you’ve seen and probably even used most of these point of views.

While these are the only types of POV, there are additional narrative techniques you can use to tell an interesting story. To learn how to use devices like epistolary and framing stories, check out our full narrative devices guide here.

Let’s discuss each of the four types, using examples to see how they affect your story. We’ll also go over the rules for each type, but first let me explain the big mistake you don’t want to make with point of view.

The #1 POV Mistake

“

Once you pick a point of view, you’re stuck with it.

Do not begin your story with a first person narrator and then switch to a third person narrator. Do not start with third person limited and then abruptly give your narrator full omniscience.

The guideline I learned in my first creative writing class in college is a good one:

Establish the point of view within the first two paragraphs of your story.

And above all, don’t change your point of view. If you do, it creates a jarring experience for the reader and you’ll threaten your reader’s trust. You could even fracture the architecture of your story.

That being said, as long as you’re consistent, you can sometimes get away with using multiple POV types. This isn’t easy and isn’t recommended, but for example, one of my favorite stories, a 7,000 page web serial called Worm, uses two point of views—first person with interludes of third-person limited—very effectively. (By the way, if you’re looking for a novel to read over the next two to six months, I highly recommend it—here’s the link to read for free online.) The first time the author switched point of views, he nearly lost my trust. However, he kept this dual-POV consistent over 7,000 pages and made it work.

Whatever point of view choices you make, be consistent. Your readers will thank you!

Now, let’s go into detail on each of the four narrative perspective types, their best practices, and mistakes to avoid.

First Person Point of View

In first person point of view, the narrator is in the story and telling the events he or she is personally experiencing.

The simplest way to understand first person is that the narrative will use first-person pronouns like I, me, and my.

Here’s a first person point of view example from Herman Melville’s Moby Dick:

Call me Ishmael. Some years ago—never mind how long precisely—having little or no money in my purse, and nothing particular to interest me on shore, I thought I would sail about a little and see the watery part of the world

First person narrative perspective is one of the most common POVs in fiction. If you haven’t read a book in first person point of view, you haven’t been reading.

What makes this point of view interesting, and challenging, is that all of the events in the story are filtered through the narrator and explained in his or her own unique narrative voice.

This means first person narrative is both biased and incomplete.

Other first person point of view examples can be found in these popular novels:

- The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway

- Twilight by Stephenie Meyer

- Ready Player One by Ernest Cline

- The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins

- The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

“

If you haven’t read a book in first person point of view, you haven’t been reading.

First Person Narrative is Unique to Writing

There’s no such thing as first person in film or theater—although voiceovers and mockumentary interviews like the ones in The Office and Modern Family provide a level of first person narrative in third person perspective film and television.

In fact, the very first novels were written in first person, modeled after popular journals and autobiographies.

First Person Point of View is Limited

First person narrators are narrated from a single character’s perspective at a time. They cannot be everywhere at once and thus cannot get all sides of the story.

They are telling their story, not necessarily the story.

First Person Point of View is Biased

In first person novels, the reader almost always sympathizes with a first person narrator, even if the narrator is an anti-hero with major flaws.

Of course, this is why we love first person narrative, because it’s imbued with the character’s personality, their unique perspective on the world.

The most extreme use of this bias is called an unreliable narrator. Unreliable narration is a technique used by novelists to surprise the reader by capitalize on the limitations of first person narration to make the narrator’s version of events extremely prejudicial to their side and/or highly separated from reality.

You’ll notice this form of narration being used when you, as the reader or audience, discover that you can’t trust the narrator.

For example, Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl pits two unreliable narrators against one another. Each relates their conflicting version of events, one through typical narration and the other through journal entries. Another example is Fight Club, in which *SPOILER* the narrator has a split personality and imagines another character who drives the plot.

Other Interesting Uses of First Person Narrative:

- The classic novel Heart of Darkness is actually a first person narrative within a first person narrative. The narrator recounts verbatim the story Charles Marlow tells about his trip up the Congo river while they sit at port in England.

- William Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom is told from the first person point of view of Quentin Compson; however, most of the story is a third person account of Thomas Sutpen, his grandfather, as told to Quentin by Rosa Coldfield. Yes, it’s just as complicated as it sounds!

- Salman Rushdie’s award-winning Midnight’s Children is told in first person, but spends most of the first several hundred pages giving a precise third person account of the narrator’s ancestors. It’s still first person, just a first person narrator telling a story about someone else.

Two Big Mistakes Writers Make with First Person Point of View

When writing in first person, there are two major mistakes writers make:

1. The narrator isn’t likable. Your protagonist doesn’t have to be a cliché hero. She doesn’t even need to be good. However, she must be interesting.

The audience will not stick around for 300 pages listening to a character they don’t enjoy. This is one reason why anti-heroes make great first person narrators.

They may not be morally perfect, but they’re almost always interesting.

2. The narrator tells but doesn’t show. The danger with first person is that you could spend too much time in your character’s head, explaining what he’s thinking and how he feels about the situation.

You’re allowed to mention the character’s mood, but don’t forget that your reader’s trust and attention relies on what your character does, not what he thinks about doing.

Second Person Point of View

While not used often in fiction—it is used regularly in nonfiction, song lyrics, and even video games—second person POV is still helpful to understand.

In this point of view, the narrator relates the experiences using second person pronouns like you and your. Thus, you become the protagonist, you carry the plot, and your fate determines the story.

We’ve written elsewhere about why you should try writing in second person, but in short we like second person because it:

- Pulls the reader into the action of the story

- Makes the story personal

- Surprises the reader

- Stretches your skills as a writer

Here’s an example from the breakout bestseller Bright Lights, Big City by Jay Mclnerney (probably the most popular example that uses second person point of view):

You have friends who actually care about you and speak the language of the inner self. You have avoided them of late. Your soul is as disheveled as your apartment, and until you can clean it up a little you don’t want to invite anyone inside.

Second person narration isn’t used frequently, however there are some notable examples of it.

Some other novels that use second person point of view are:

- Remember the Choose Your Own Adventure series? If you’ve ever read one of these novels where you get to decide the fate of the character (I always killed my character, unfortunately), you’ve read second person narrative.

- The Fifth Season by N.K. Jemison

- The opening of The Night Circus by Erin Morgenstern

There are also many experimental novels and short stories that use second person, and writers such as William Faulkner, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Albert Camus played with the style.

Breaking the fourth wall:

In the plays of William Shakespeare, a character will sometimes turn toward the audience and speak directly to them. In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Puck says:

If we shadows have offended, think but this, and all is mended, that you have but slumbered here while these visions did appear.

This narrative device of speaking directly to the audience or the reader is called breaking the fourth wall (the other three walls being the setting of the story).

To think of it another way, it’s a way the writer can briefly use second person in a first or third person narrative.

It’s a lot of fun! You should try it.

Third Person Point of View

In third person narration, the narrator is outside of the story and relating the experiences of a character.

The central character is not the narrator. In fact, the narrator is not present in the story at all.

The simplest way to understand third person narration is that it uses third-person pronouns, like he/she, his/hers, they/theirs.

There are two types of this point of view:

Third Person Omniscient

The all-knowing narrator has full access to all the thoughts and experiences of all the characters in the story.

Examples of Third Person Omniscient:

While much less common today, third person omniscient narration was once the predominant type, used by most classic authors. Here are some of the novels using omniscient perspective today.

- War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy

- Middlemarch by George Eliot

- Where the Crawdad’s Sing by Delia Owens

- The Old Man and the Sea by Ernest Hemingway

- Still Life by Louise Penny (and all the Inspector Gamache series, which is amazing, by the way)

- Gossip Girl by Cecily von Ziegesar

- Strange the Dreamer by Laini Taylor

- Little Women by Louisa May Alcott

- Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan (one of my favorites!)

- A Wizard of Earthsea by Ursula Le Guin

- Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

- More third person omniscient examples can be found here

Third Person Limited

The narrator has only some, if any, access to the thoughts and experiences of the characters in the story, often just to one character.

Examples of Third Person Limited

Here’s an example of a third person limited narrator from Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone by J.K. Rowling:

A breeze ruffled the neat hedges of Privet Drive, which lay silent and tidy under the inky sky, the very last place you would expect astonishing things to happen. Harry Potter rolled over inside his blankets without waking up. One small hand closed on the letter beside him and he slept on, not knowing he was special, not knowing he was famous…. He couldn’t know that at this very moment, people meeting in secret all over the country were holding up their glasses and saying in hushed voices: “To Harry Potter—the boy who lived!”

Some other examples of third person limited narration include:

- Game of Thrones series by George R.R. Martin (this has an ensemble cast, but Martin stays in one character’s point of view at a time, making it a clear example of limited POV with multiple viewpoint characters, which we’ll talk about in just a moment)

- For Whom the Bell Tolls by Ernest Hemingway

- The Way of Kings by Brandon Sanderson

- The Da Vinci Code by Dan Brown

- The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo by Stieg Larsson

- Ulysses by James Joyce

- Love in the Time of Cholera by Gabriel Garcia Marquez

- 1984 by George Orwell

- Orphan Train by Christina Baker Kline

- Fates and Furies by Lauren Groff

Should You Use Multiple Viewpoint Characters vs. a Single Perspective?

One feature of third person limited and first person narrative is that you have the option of having multiple viewpoint characters.

A viewpoint character is simply the character whose thoughts the reader has access to. This character become the focus of the perspective during the section of story or the story as a whole.

While it increases the difficulty, you can have multiple viewpoint characters for each narrative. For example, Game of Thrones has more than a dozen viewpoint characters throughout the series. Fifth Season has three viewpoint characters. Most romance novels have at least two viewpoint characters.

The rule is to only focus on one viewpoint character at a time (or else it changes to third person omniscient).

Usually authors with multiple viewpoint characters will change viewpoints every chapter. Some will change after section breaks. However, make sure there is some kind of break before changing so as to prepare the reader for the shift.

Should You Use Third Person Omniscient or Third Person Limited

The distinction between third persons limited and omniscient is messy and somewhat artificial.

Full omniscience in novels is rare—it’s almost always limited in some way—if only because the human mind isn’t comfortable handling all the thoughts and emotions of multiple people at once.

The most important consideration in third person point of view is this:

How omniscient are you going to be? How deep are you going to go into your character’s mind? Will you read their thoughts frequently and deeply at any chance? Or will you rarely, if ever, delve into their emotions?

To see this question in action, imagine a couple having an argument.

Tina wants Fred to go to the store to pickup the cilantro she forgot she needed for the meal she’s cooking. Fred is frustrated that she didn’t ask him to pick up the cilantro on the way home from the office, before he had changed into his “homey” clothes (AKA boxer shorts).

If the narrator is fully omniscient, do you parse both Fred and Tina’s emotions during each back and forth?

“Do you want to eat? If you do, then you need to get cilantro instead of acting like a lazy pig,” Tina said, thinking, I can’t believe I married this jerk. At least back then he had a six pack, not this hairy potbelly.

“Figure it out, Tina. I’m sick of rushing to the store every time you forget something,” said Fred. He felt the anger pulsing through his large belly.

Going back and forth between multiple characters’ emotions like this can give a reader whiplash, especially if this pattern continued over several pages and with more than two characters. This is an example of an omniscient narrator who perhaps is a little too comfortable explaining the characters’ inner workings.

“Show, don’t tell,” we’re told. Sharing all the emotions of all your characters can become distraction. It can even destroy any tension you’ve built.

Drama requires mystery. If the reader knows each character’s emotions all the time, there will be no space for drama.

How do You Handle Third Person Omniscient Well?

The way many editors and many famous authors handle this is to show the thoughts and emotions of only one character per scene (or per chapter).

George R.R. Martin, for example, uses “point of view characters,” characters whom he always has full access to understanding. He will write a full chapter from their perspective before switching to the next point of view character.

For the rest of the cast, he stays out of their heads.

This is an effective guideline, if not a strict rule, and it’s one I would suggest to any first-time author experimenting with third person narrative. Overall, though, the principle to show, don’t tell should be your guide.

The Biggest Third Person Omniscient Point of View Mistake

The biggest mistake I see writers make constantly in third person is head hopping.

When you switch point of view characters too quickly, or dive into the heads of too many characters at once, you could be in danger of what editors call “head hopping.”

When the narrator switches from one character’s thoughts to another’s too quickly, it can jar the reader and break the intimacy with the scene’s main character.

We’ve written about how you can get away with head hopping elsewhere, but it’s a good idea to try to avoid going into more than one character’s thoughts per scene or per chapter.

Can You Change POV Between Books In a Series?

What if you’re writing a novel series? Can you change point of view or even POV characters between books?

The answer is yes, you can, but whether you should or not is the big question.

In general, it’s best to keep your POV consistent within the same series. However, there are many examples of series that have altered perspectives or POV characters between series, either because the character in the previous books has died, for other plot reasons, or simply because of author choice.

For more on this, watch this coaching video where we get into how and why to change POV characters between books in a series:

Which Point of View Will You Use?

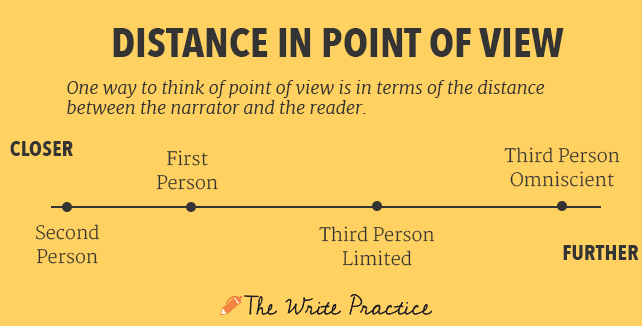

Here’s a helpful point of view infographic to help you decide which POV to use in your writing:

Note that these distances should be thought of as ranges, not precise calculations. A third person narrator could conceivably draw closer to the reader than a first person narrator.

Most importantly, there is no best point of view. All of these points of view are effective in various types of stories.

If you’re just getting started, I would encourage you to use either first person or third person limited point of view because they’re easy to understand.

However, that shouldn’t stop you from experimenting. After all, you’ll only get comfortable with other points of view by trying them!

Whatever you choose, be consistent. Avoid the mistakes I mentioned under each point of view.

And above all, have fun!

Need help with point of view? To get a cheatsheet of the two most common POVs used in fiction, click here.

Need help with point of view? To get a cheatsheet of the two most common POVs used in fiction, click here.

How about you? Which of the four points of view have you used in your writing? Why did you use it, and what did you like about it? Share in the comments.

PRACTICE

Using a point of view you’ve never used before, write a brief story about a teenager who has just discovered he or she has superpowers.

Make sure to avoid the POV mistakes listed in the article above.

Write for fifteen minutes. When your time is up, post your practice in the Pro Practice Workshop here. And if you post, please be sure to give feedback to your fellow writers.

We can gain just as much value giving feedback as we can writing our own books!

Happy writing!