The 10 Sorts of Tales and The right way to Grasp Them

How do you write a best-selling novel or an award-winning screenplay? You might say, great writing or unique characters or thrilling conflict. But so much of writing a great story is knowing and mastering the type of story you’re trying to tell.

What are the types of stories? And how do you use them to tell a great story?

In this article, we’re going to cover the ten types of stories, share which tend to become best-sellers, and share the hidden values that help you master each type.

But first, what do I mean by “types of stories”?

Want to learn more about plot types and story structure? My #1 Amazon best-selling book The Write Structure explores the hidden structures behind bestselling and award-winning stories. If you want to learn more about how to write a great story, by mastering storytelling musts like the exposition literary definition, you can get the book for a limited time low price. Click here to get The Write Structure ($5.99).

Definition of Story Types

As stories have evolved for thousands of years, they began to fall into patterns called story types. These types tend to operate on the same underlying values. They also share similar structures, characters, and what Robert McKee calls obligatory scenes.

But Wait, Do Story Types Really Exist?

First, I want to address some discomfort you might be feeling with this idea. If you think that stories are magical and mystical, and the idea of putting them in a box feels terrible to you, I just want to say, I get that. I feel like that about stories, too!

You see, there are two ways you can figure out the patterns that stories take—the different types of stories.

You can start with stories themselves: looking through hundreds or even thousands until you get to four, seven, twelve, or even thirty-six master plots. This is what Christopher Booker did with his excellent guide The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories, and you can get breakdowns of each of his types here.

And that can be helpful, certainly, but what about stories that are a little strange, genre-breaking, or out of the box?

Do they not have a “type”?

The other way you can figure out the types of stories is by going deeper, to the underlying reasons humans tell stories in the first place, the reason we’ve been telling stories for thousands of years, all the way back to the campfire stories our ancestors told each other.

Why do we tell stories? The reason humans have always told stories (and always will) is because we want something.

Maybe we want something as simple as to stay alive. This was one reason our long-ago ancestors told stories about surviving attacks from ferocious beasts.

Maybe we want love or belonging, so we tell great love stories about couples destined (or doomed) to be together.

Maybe we want to become the best version of ourselves. We tell stories about how people have overcome adversity, even pushed back against their narrow-minded communities, to fully self-actualize.

Or maybe we want to tell stories about what it’s like to transcend, to go beyond yourself and your circumstances and serve the good of the whole community, the whole world, and so we tell stories about sacrifice and great heroism.

In other words, basic story types arise from values, from the things humans want, and the great thing is, there has been a lot of research into the values humans find to be universal.

Story Types Are Defined by 6 Values

Great, bestselling stories are about values.

Value Definition

Value, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, is the regard that something is held to deserve; the importance, worth, or usefulness of something.

In other words, a value is something you admire, something you want. If you value something, it means you think it’s good.

Values in Stories

Here are some examples of things you might value:

- Money

- Friends

- A sibling

- Education

- Organization

- Justice

- Compassion

- Ferraris

- Environment

- Honor

- Courage

- Productivity

- Power

- Humility

This could easily become a never-ending list.

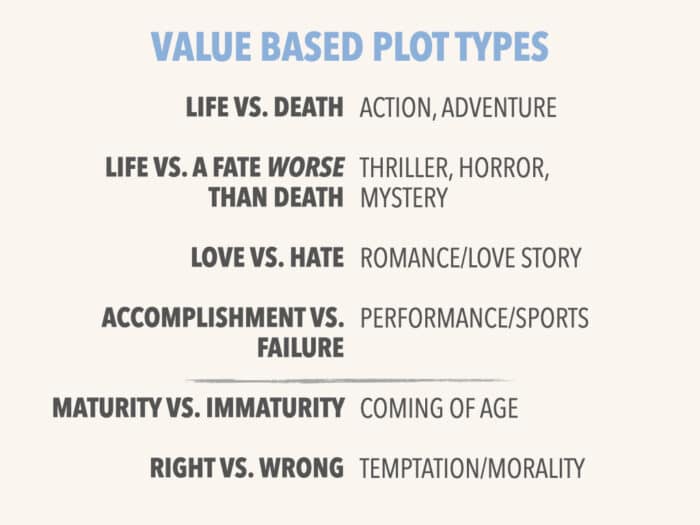

But if you think about it, every value can be distilled to six essential human values. Building off of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, these values are as follows (credit to Robert McKee and Shawn Coyne for introducing me to these concepts):

- Survival from Nature. The value of life. Because if you don’t have your life, you don’t have much.

- Survival from Others. Surviving crime, other people, even monsters, you could say.

- Love/Community. The value of human connection.

- Esteem. The value of your status and hierarchy within a community.

- Personal Growth. The value of reaching your potential.

- Transcendence. The value of going beyond yourself to discover a larger purpose.

Once you distill these values, you can turn these values into scales, because these values are usually in conflict with their opposite.

- Survival from Nature > Life vs. Death

- Survival from Others > Life vs. Fate Worse than Death

- Love/Community > Love vs. Hate

- Esteem > Accomplishment vs. Failure

- Personal Growth > Maturity vs. Immaturity

- Transcendence > Right vs. Wrong

In fact, it is the conflict between these values that generate the movement and change that makes the story work.

These are the same values that drive good storytelling.

If you take them a step further you can take these value scales and map them to different types of stories—or plot types. Here’s how it works:

- Life vs. Death: Adventure, Action Stories

- Life vs. Fate Worse than Death: Thriller, Horror, Mystery Stories

- Love vs. Hate: Romance/Love Stories

- Accomplishment vs. Failure: Performance/Sports Stories

- Maturity vs. Immaturity: Coming of Age stories

- Right vs. Wrong: Temptation/Morality Stories

These plot types transcend literary genre. You can have a sci-fi love story, a historical thriller, a fantasy performance story, a mystery romance story, or even a young adult adventure story. (For more, check out my guide on literary genres here.)

“

Don’t mistake types of stories with genre. Plot types transcend genre. In this article, learn about the 10 types of stories and how to write them.

Your story’s plot type will determine much of your story: the scenes you must include, the conventions and tropes you employ, your characters (including protagonists, side characters, and antagonists), and more.

How does that work practically? Let’s look at a couple of examples:

Adventure Story Type Example

Let’s look at a classic example, The Hobbit, one of the best-selling novels of all time, by J.R.R. Tolkien.

When you’re trying to understand the type of story you’re trying to tell, the first question to ask is, “What value scale do a majority of the scenes move on?”

The question constantly coming up in The Hobbit is this: “Is Bilbo Baggins going to survive the run-ins with the spiders and trolls and orcs, or is he not going to survive?”

The Hobbit, at its core, is an adventure story, and that means that a majority of the scenes move on the Life vs. Death Scale.

While there are certainly scenes that fall on the Good vs. Evil and Maturity vs. Naïveté scales, it is the Life vs. Death scale that most of the scenes move on.

The 10 Types of Stories

Now that we’ve looked at an example, let’s break down each of the ten main story types and talk about how they work.

Each of these plot types has typical archetypes for their inciting incidents and main event/climax. While you can certainly tweak or even re-work these archetypes, it’s best to understand how they work and ensure that your new version of the event can bring out as much of the conflict as the typical method.

For more on this, check out our respective guides on inciting incidents and climaxes.

These ideas are not new, and I also have to acknowledge a huge debt to the story theorists who have gone before me, especially Blake Snyder, author of Save the Cat; Robert McKee, author of Story; and Shawn Coyne, author of Story Grid.

“

There are 10 types of stories that a story can fall under. Learn them (with examples) in this article, and figure out the kind of story you are writing.

1. Adventure Story Type

Value: Life vs. Death

Inciting Incident Archetype(s): The Quest for the MacGuffin. A MacGuffin is an object, place, or (sometimes) person of great importance to the characters of the story, and the thing that drives the plot. For example, the ring in Lord of the Rings, the horcruxes in Harry Potter, or the ark of the covenant in Indiana Jones. Most adventure plot types revolve around a MacGuffin, and the inciting incident involves introducing the MacGuffin and its importance.

Main Event: Final showdown with the bad guys (while trying to get the MacGuffin).

Examples: The Odyssey, The Lord of the Rings, The Hobbit, Beowulf, Alice in Wonderland

Note: Most (but not all) hero’s journey stories fit this type, as well as any “voyage and return” type plots.

2. Action Story Type

Value: Life vs. Death

Inciting Incident Archetype(s):

- Great Crime Against Me. Many action plots begin with some kind of wrong done to the protagonist, usually but not always by the chief antagonist. This begins the action of the story as the protagonist seeks to right this wrong or, often, get revenge.

- The Emergence of a Great Evil. An alternative inciting incident involves the emergence of some kind of great evil. This may be another character like an antagonist, a natural force or disaster, or some kind of other creature. The emergence of this evil thing creates a need for the protagonist to respond urgently.

Main event: Showdown with the Bad Guy

Examples: The Count of Monte Cristo, Hunger Games

3. Horror Story Type

Value: Life vs. Fate Worse than Death

Inciting Incident Archetype(s):

- Forbidden Object/Act. Many horror stories begin with the main character doing some kind of forbidden thing, whether stealing a forbidden object or causing the death of someone else, which leads to a reprisal, often in the form of a monstrous creature, being, or person.

- “Monster in the House.” This plot type, coined by Blake Snyder of Save the Cat, begins when the characters are trapped within some kind of space—often a house but potentially any limited amount of space like a city or even the world as a whole—with some kind of monstrous creature, being, or person.

Main Event: Confrontation of the Monster

Examples: The Shining, The Exorcist, The Haunting of Hill House, The Grudge, Candyman, Macbeth

4. Thriller Story Type

Value: Life vs. a Fate Worse than Death

The thriller plot type is closely related to the Action and Mystery plot types. Both begin with some kind of crime, contain investigative elements, and climax with the hero at the mercy of the villain.

However, what makes it unique is there is always a horror element, a sense that this is somehow worse, more monstrous, than your average crime.

It’s a fine line, though, and many story theories, like those from Robert McKee, make no distinction between the Thriller with the Action plot types.

Inciting Incident Archetype(s): Show me the (Monstrously Brutalized) Body. As with the mystery plot type (below), Thriller plot types contain an inciting incident in which a crime is discovered, whether it’s a literal dead body, a theft, or some other type of crime. However, with thriller, the crime has a horror feel to it, the crime being particularly monstrous, brutal, etc.

Main Event: Hero at the Mercy of the Villain. In the climactic scene, the main character is caught by the antagonist and at their mercy, showing their (temporary) dominance. Depending on the story arc, the protagonist may reverse their situation or succumb to the antagonist.

5. Mystery Story Type

Value: Life vs. Fate Worse than Death (in the sense of a restoration of Justice)

Inciting Incident Archetype(s): Show Me the Body. All mystery plot types contain an inciting incident in which a crime is discovered, whether it’s a literal dead body, a theft, or some other type of crime.

Main Event: The Confession. The antagonist confesses to the crime and justice, the power of life over death, is restored.

Examples: The Inspector Gamache series, Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (as a subplot)

6. Romance/Love Story Type

Value: Love vs. Hate

Inciting Incident Archetype(s): Meet Cute OR We Should Break Up. Love plots either begin with the couple meeting or breaking up/getting into some kind of conflict. The meet cute inciting incident involves the couple meeting in some unexpected, comedic, and/or often shambolic way, often while having extreme distaste for each other at the outset.

Main Event: Proof of Love. After some kind of separation, the protagonist must overcome obstacles to prove their love to the other.

Examples: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Romeo and Juliet, 10 Things I Hate About You and most Rom-coms

For more on writing or editing a love story, check out this coaching video:

7. Performance/Sports Story Type

Value: Accomplishment vs. Failure

The core value of the performance story type is esteem, which is all about looking good in front of your community, usually after accomplishing a great feat or winning a widely recognized competition.

Inciting Incident Archetype(s): Entry into the Big Tournament. Performance stories—whether the performance medium is sports, music, art, or some other avenue—all contain an inciting incident where the characters enter a major tournament, performance, or competition. This competition is usually an actual event (e.g. the Olympics, the state championship) but may be a less formal competition.

Main Event: The Big Tournament. After preparing for the big event by overcoming smaller obstacles throughout the story, the protagonist faces their challenger in the final competition.

Examples: Miracle, Cobra Kai, Ghost, Hamilton

8. Coming of Age Story Type

Value: Maturity vs. Immaturity

Inciting Incident Archetype(s):

- Here There Be Dragons (Confronting the Unknown). Coming of age plots often begin with an inciting incident involving something unknown, something that is outside of the protagonist’s current worldview. This throws the protagonist into confusion and shows them how much they must learn about the world.

- The Principal’s Office. Alternatively, the character may get into trouble early on, often in a school setting. This forces the character to begin the process of reflecting on his or her life and making changes.

Main Event: The Revelation. In a moment of crisis, the protagonist has a major worldview revelation, leading them to see the world in a new, more sophisticated way.

Examples: How to Train Your Dragon, Catcher in the Rye, Good Will Hunting, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, The Ugly Duckling

9. Temptation/Morality Story Type

Value: Good vs. Evil

The value of good vs. evil here is not “The Good Guys” vs. “The Bad Guys.” That plot type is usually action. Instead, the evil is within the character, and they must choose whether to do the good, self-sacrificial thing or the selfish, evil thing.

Inciting Incident Archetype(s): Let’s Make a Deal. Often temptation stories begin with a proverbial “deal with the devil,” in which the character is tempted to do something they think is relatively harmless but might give them great reward.

Main Event: Judgement Day. Facing the consequences of their actions, the main character must either embrace their consequences and change or continue to attempt to escape them and face damnation.

Examples: Wall Street, A Christmas Carol

10. Combinations (Advanced!)

While all great stories are driven by values and the conflict between them, many stories combine plot types and/or value scales in unique ways, creating new plot types of their own.

Often this approach works best with either longer works, epics that combine many arcs into one story, or shorter works, like short stories, which may not contain all the elements of longer, more established plot types.

However, combining or rearranging plot types is considered advanced. Consider before you attempt to come up with your own completely unique plot type, especially if you are a new writer, as you risk the story not working or getting lost in the plot and failing to finish.

Remember: working with an established plot type requires just as much creativity and flair for coming up with dramatic situations as invention your own.

Subtypes

While most popular stories will fit within the ten plot types above, you could also get more specific by exploring subtypes.

Subtypes are more specific plots with unique conventions, tropes, and characters. Examples of subtypes include revenge plots, a subtype of action plots; heist plots, a subplot of adventure stories; or obsession love stories.

Most stories that work will fall somewhere into the above plot types, and all stories that work will fall into the six value scales.

These 10 Types of Stories Work for Any Story Arc

Great novels, films, memoirs, and plays come in many shapes, but researchers from the University of Vermont have identified six primary shapes, all of which we talk about in detail in our story arcs guide. Here are the six:

- Rags to Riches. Happy ending story moving from negative to positive value.

- Riches to Rags. Tragic story moving from positive to negative value.

- Man in a hole. Happy ending story moving from positive to negative and back to positive.

- Icarus. Tragic story moving from negative to positive and back to negative value.

- Cinderella. Happy ending story starting negative, moving to positive, back to negative, and finally to positive again.

- Oedipus. Tragic story starting positive, moving to negative, back to positive, and finally to negative at the end.

Again, we have a full guide on the six story arcs, complete with plot diagrams, here.

These arcs are independent of plot type.

You can have a tragic Icarus mystery story where the villain gets away. You can have a Cinderella horror story where the monster starts out bad, then seems to be nearly defeated, only to come back stronger and then finally get destroyed in the end.

Even though certain genres and plot types have tendencies toward specific plotlines, the types work independently of arc. Choose any combination of the arcs and plot types, and it will still work.

2 Tips About How to Use These Plot Types

How do you actually write a book with these plot types in mind? Follow these two tips:

1. First, Know Your Values

Bad books, stories that don’t work, don’t know what their values are.

Or they’re trying to have every single value possible.

You can’t do that if you want to tell a great story. You have to choose! If you want to master the type of story you’re trying to tell, start with finding the story’s value.

Here’s a video that shows how one author figured out their plot type by diving into the value at the center of their story.

2. Focus on Conflict Between Values

You’ve heard your stories need conflict, but that doesn’t mean more arguments and car chases.

The kind of conflict your stories need more of is between values, and the way to master any type of story is to put the story’s main value in conflict with its opposite.

“

The kind of conflict your stories need more of is between values, and the way to master any type of story is to put the story’s main value in conflict with its opposite.

If you’re writing an adventure story, that means you need to have life and death moments.

If you’re writing a thriller, you need to have moments of life vs. fate worse than death.

If you’re writing a love story, you need to have as many moments of negative love, of anger, disillusion, and even hatred, as you do love.

If you’re writing a sports story, there have to be as many moments of near failure, or actual failure, as there are of success.

If you’re writing a coming-of-age story, then you need to include moments where the growing maturity of the character is put into conflict with its opposite, immaturity.

And finally, if you’re writing a temptation or morality story, then you need moments of temptation—where the character genuinely considers if they should take actions they know are wrong because of how it could benefit them or solve a greater problem.

So how about you? What type of story are you trying to tell? Let us know in the comments.

PRACTICE

Put the types of story to use now with the following creative writing exercise.

First, choose one of the story scales above.

Then, outline the inciting incident scene or another scene in which your protagonist is faced with the negative value in that scale.

Finally, set a timer for fifteen minutes. Write as much of your scene as you can.

When your time is up, post your scene in the Pro Practice Workshop here. And when you’re done, check out others who have shared their scenes. Let them know what you think!

Not a member yet? Come join us here. We’re a group of writers committed to practicing together.