What Is Plot? The 6 Parts of Plot and Tips on how to Use Them

You want readers to love your story, to pick up your book and be so immersed they won’t be able to put it down.

To do that, though, you need to have a great plot. But what is plot, and how do you craft one into a great story?

In this guide, we’re going to talk about plot in literature. I’ll share a broad definition of plot, then dive into the approach we use at The Write Practice (called The Write Structure), and finally you’ll learn the six elements of plot that make stories entertaining and memorable.

To do this, we’ll look at a few examples of how these elements work in bestselling stories. We’ll touch on story arcs, the different shapes a plot of a story can take. We’ll also look at several plot diagrams to better understand how plot works visually. Finally, you’ll learn exactly how you can use your new understanding of plot in your own stories.

You can read the guide below or watch the video lesson here:

This article contains an excerpt from our book The Write Structure, which is a timeless approach to storytelling and structure. You can learn more about it here.

What Is Plot? Plot Definition

Plot is a sequence of events in a story in which the main character is put into a challenging situation that forces them to make increasingly difficult choices, driving the story toward a climactic event and resolution.

What are the 6 Elements of Plot and Structure

We will define each below, but here are the six elements of plot:

These elements are the major events in a story, and they’re essential in all creative writing, whether you’re writing a novel, screenplay, memoir, short story, or other form. Even skilled writers who do not use these intentionally are incorporating them into their writing subconsciously because they are what brings movement, conflict, action, and life to stories.

You can learn more about each below or in my new book, The Write Structure.

Story vs. Plot

There’s a difference between story and plot, something author E.M. Forster makes a distinction between in his book, Aspects of the Novel.

A story is just an event, almost a recitation of facts. The mouse ate a cookie isn’t a plot—it’s just a story (albeit a cute story).

A plot, requires cause and effect. The mouse ate a cookie and then asked for a glass of milk is a plot because it’s causal. I’ll let Forster explain it better:

“Let us define plot. We have defined a story as a narrative of events arranged in their time-sequence. A plot is also a narrative of events, the emphasis falling on causality. ‘The king died and then the queen died,’ is a story. ‘The king died, and then the queen died of grief,’ is a plot. The time-sequence is preserved, but the sense of causality overshadows it. Or again: ‘The queen died, no one knew why, until it was discovered that it was through grief at the death of the king.’ This is a plot with a mystery in it…”

– E. M. Forster

To trim that down:

- The king died and then the queen died is a story.

- The king died and then the queen died of grief is a plot because it’s causal and connected.

Hemingway’s famous six-word story is an amazing example of plot: “For sale: baby shoes, never worn.” Why are they for sale? Because the baby never wore them (and oh, it’s so sad). These aren’t disconnected facts; this is actually a miniature plot. More on that in a moment.

How Plot Works

Plot has a specific structure. It follows a format that sucks readers in; introduces characters, character development, and world building; and compels readers to keep reading in order to satisfy conflict and answer questions.

Plot is about cause and effect, but, most importantly, plot is about choice: a character’s choice.

In other words, it’s not just a recitation of facts; the facts you include in your plot each have a purpose, putting a character into a situation where they must make a decision and pulling the story toward its conclusion.

The 6 Elements of Plot

So how do you build a plot with this cause-and-effect thing? Fortunately, the answer is simple: you break plot down into its components.

“

Plot is a series of events in a story in which the main character is put into a challenging situation that forces a character to make increasingly difficult choices, driving the story toward a climactic event and resolution.

The components of plot are like puzzle pieces. If you want your reader to see the final picture, you need to see the shape of each component and fit them into their proper place.

Does anyone else feel like this puzzle piece is closing a hole in the universe or something? Just me? Too much Dr. Who, I guess.

In The Write Structure, we talk about the six elements of plot:

1. Exposition. At the beginning of the story, the exposition establishes characters and setting. Not all your world-building happens here, but this is where you show your readers what “normal” is for your characters. That way, readers will know what’s wrong when we hit the next step. Learn more in our full exposition guide here.

2. Inciting Incident. The inciting incident is an event in a story that throws the main character into a challenging situation, upsetting the status quo and beginning the story’s movement, either in a positive or negative way. This movement culminates in the climax and denouement. Learn more in our full inciting incident guide here.

3. Rising action, or Progressive Complications. This is the largest part of the story, and where most of the conflict takes place. You know that quote about getting your characters up a tree, then throwing rocks at them? This is rock-throwing time. Here’s where you raise the stakes and begin building up to the story’s climax. It’s crucial that your readers know what’s at stake here; it’s also critical that they clearly understand the conflict. Learn more our full rising action guide here.

4. Dilemma (or crisis, according to Story Grid). This is the most important element, what you’ve been building toward, the moment when a character is put into a situation where they must make an impossible choice. Learn more in our full dilemma guide here.

5. Climax. This is the big moment! The character’s choice from the dilemma drives the outcome of the conflict. If you did it right, this is the worst (i.e. best) moment of tension in the whole story, setting your readers on edge. Learn more in our full climax guide here.

6. Denouement or Resolution. Now, at the end of the story, you’re establishing “normal” all over again—but the new normal, incorporating the changes and experiences of your characters. Your readers can sit with your characters a little in their new normal, emotionally wrapping everything up so your reader can put the book away without flipping back through the pages to see what they missed. It’s a scene-closure with enough finality to deserve those two words: The End. Learn more in our full denouement guide here.

Historical Note: One of the earliest writers to talk about this structure was Gustav Freytag, the German author who wrote in the middle of the 19th century. His basic structure became known as Freytag’s Pyramid, and he was the first to talk about many of five elements of plot we discuss above.

While we salute Freytag for bringing language to these plot points, we believe Freytag’s Pyramid is an outdated and misunderstood plot framework. You can read more about Freytag’s Pyramid and whether you should use it in our guide on the five act structure here.

How to Create a Plot Outline: Start With the 6 Elements

The cool thing about those six elements is that they can make up your first six plot points when you’re creating an outline.

In fact, putting together a plot outline doesn’t have to be complicated, all you need are six sentences, one for each element, and you’ll have a strong outline to begin your story with.

Give it a try in the Practice section below!

What about the Falling Action?

In The Write Structure, the plot framework we’ve developed at The Write Practice, we don’t use the plot point falling action, which you might see in other frameworks.

Why do exclude it?

Falling action is usually described as the events to wind down the plot after the climax, but in most stories, the climax happens near the end of a story, usually in the third to last scene. Thus, the falling action and denouement are virtually indistinguishable.

To avoid confusion, we believe the falling action should be phased out from use as an element of plot.

You can learn more about why we don’t consider falling action a plot element here.

Do Short Stories Have These Elements?

Yes! In fact, every scene and every act in a story should have each of these elements as well.

In a short story, however, these elements will be necessarily abbreviated. For example, where rising action might have many complications in a novel, it might only have one complication in a short story.

What Is a Plot Type: Stories Come In 10 Types

Stories have been told for thousands of years, and as they have evolved, they have started to fall into patterns, patterns we call plot types or story types.

These types of plot tend to be about the same underlying, universal values and share similar structures, characters, and what Robert McKee calls obligatory scenes.

There are 10 major plot types:

- Adventure

- Action

- Horror

- Thriller

- Mystery

- Love/Romance

- Performance/Sports

- Coming of Age

- Temptation/Morality

- Combo

While plot types are related to genre, they also transcend genre and have been consistent throughout history, dealing with the timeless, universal values behind stories.

We fully explore these values, each of these ten plot types, in our complete Plot Types guide here.

What Is a Plot Diagram: Story Arcs Can Have Many Shapes

While all plots have a set structure, they can have many shapes or arcs. These arcs can be visualized in a plot diagram, like those below.

Plot Diagram Definition

A plot diagram is a visual representation of a story on an axis.

Here are five of the most common story arcs, visualized in plot diagrams. For more on each of these, check out our complete story arcs guide here.

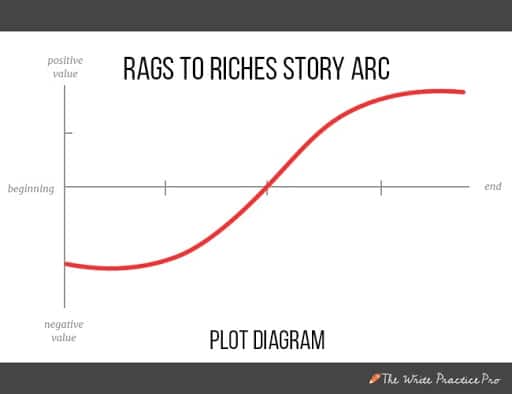

Rags to Riches Plot Diagram

Rags to riches is one of the most basic plot diagrams. A character starts in a bad place at the start and things get better and better.

Here’s how the plot points work in rags to riches:

- The exposition sets up the protagonist’s generally negative situation in life.

- The inciting incident presents an exciting opportunity to improve their life, in some way.

- During the rising action, things are getting better, but also more complicated, with new problems, and (likely) villains, constantly appearing, threatening all their gains.

- In the dilemma, the protagonist faces an impossible choice, likely about how to keep all their gains or risk losing them.

- The climax plays out the choice the protagonist makes, and how they ultimately triumph.

- The denouement resolves the plot with a happy ending.

This is a relatively simple plot diagram. Now, let’s look at a few more complicated shapes.

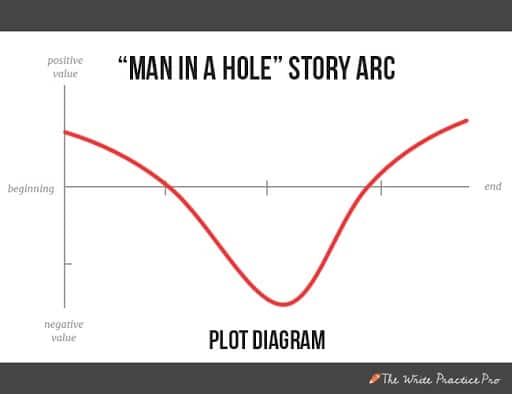

Man In a Hole Plot Diagram

In a “man in a hole” story arc, a common arc, the main character starts out in a good place, gets into trouble, and then gets themself out of it, to finish the story with a happy ending.

Here’s how the plot points work for a man in a hole arc:

- The exposition sets up the character’s generally good situation in life.

- The inciting incident pushes the character into a hole, a problem that worsens throughout the rising action.

- The rising action contains all of the plot between the descent into the hole to the character getting themself out of it. The turning point of the story comes at some point in the middle of the rising action (sometimes called the midpoint) when the main character begins to get themself out of the hole.

- However, the main character faces a final dilemma, one that threatens to push them back into the hole.

- In the climax, they finally climb all the way out of the hole.

- In the denouement, we see the resolution of their situation and how they’re once again enjoying their lives.

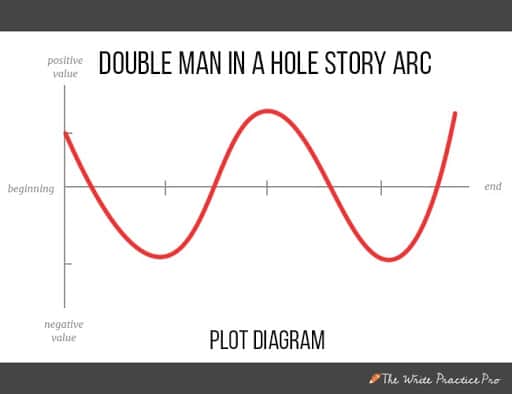

Related to the man in a hole arc is the “double man in a hole” arc.

Double Man In a Hole Plot Diagram

Building upon the “man in a hole” arc is the “double man in a hole” arc, one of the most popular shapes for stories, appearing in many bestselling novels and blockbuster films. Like man in a hole, it begins with a character who is in a great place, but soon gets into trouble. They get themself out of trouble, but then they get back into trouble again. Finally, they get back out of trouble, and the story ends with a happy ending.

Here’s how the plot elements work in this arc:

- The exposition, as always, introduces us to the protagonist, their world, and the elements that will soon interrupt their general well-being.

- Like the man in the hole story arc, the inciting incident in a double man in a hole arc pushes the main character into a hole, a problem or situation.

- The rising action of this story arc contains a lot of movement, as the problem worsens before reaching a turning point (sometimes called a pinch point) when things begin to improve before reaching the midpoint. However, in the things soon after descend into another hole, perhaps caused by the same problem or a new one.

- The dilemma occurs at some point in this second hole, likely at or near the bottom.

- This is followed by the climax, in which the protagonist’s choice plays out.

- The denouement resolves the story with a happy ending.

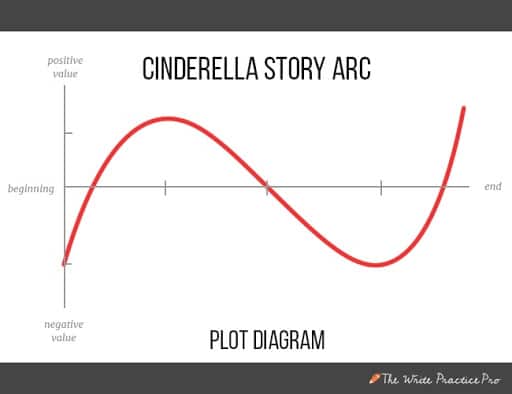

Cinderella Plot Diagram

Another story arc with a happy ending, one especially popular in romantic comedies, is the Cinderella arc.

Here’s how it works with the six elements:

- In the exposition, the main character is in a very bad place.

- The inciting incident is actually a positive event, often a meet cute or a potential opportunity.

- From there, the character slowly improves their station through the rising action, until a turning point flips them back to their original low and perhaps beyond.

- The dilemma often occurs in a “dark night of the soul” place or immediately after.

- This is followed by a climax in which the character’s fortunes dramatically rise.

- The denouement resolves the story with a happy ending.

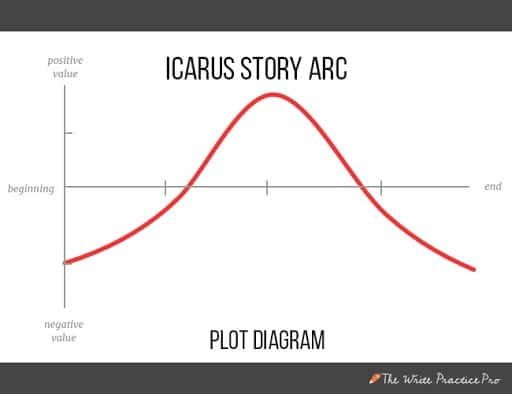

Icarus Plot Diagram

The Icarus arc is quintessential tragedy.

The plot elements usually are usually arranged like this:

- The protagonist begins low in the exposition.

- Their fortunes begin to improve after an inciting incident.

- Things continue to improve in the rising action, culminating in a midpoint turning point, when things begin to go terribly wrong. As the protagonist struggles to hold on to their good fortune.

- The unravelling increases right up to the dilemma, which ultimately seals their fate.

- The final, inevitable tragic climax confirms the tragedy.

- The denouement “resolves” the plot with the characters, and audience, reflecting on the result.

This last plot diagram might look the most recognizable, since it’s the shape that is used most in plots, originating with Freytag himself.

However, it’s built on a misunderstanding of how plots move. All stories do not follow this exact shape, and by forcing stories into this shape, we only cause confusion.

The one requirement is that a story must move, there must be some kind of change, but the shape that story takes is widely variable.

For more on this, including the six main shapes stories can take, plus the three bestselling story arcs, check out our full story arc guide here.

Can Your Story Have More than One Plot? Main Plots, Subplots, and Internal Plots

Most great stories, if you dissect them, are made up of not one but two or three plots. You have:

- The Main Plot, which contains most of the scenes of the story

- The Subplot, while not the main plot, usually deepens the story and adds another dimension (love stories make up roughly ninety percent of subplots)

- The Internal Plot, which shows the development of the main character as they grow in maturity or selflessness

If you want to learn more about how to use subplots, I recommend checking out our full subplot guide here.

The Components of Plot: Examples

Let’s look at a few examples of plot elements at work in two well known stories.

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone by J. K. Rowling

Also known as Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone to those familiar with the U.K. version.

- Exposition: We’re introduced to the Dursleys and to Harry, our protagonist and main character.

- Inciting Incident: Harry is sent a letter that, we learn later, accepts him into Hogwarts, an academy of magic, sending the Dursleys, who deny the existence of magic, into a fit, and causing Mr. Dursley to confiscate the letters.

- Rising action/progressive complications: We meet Hagrid who puts an end to the Dursley’s reign of terror; we go shopping for school supplies; we learn about Voldemort; we arrive in Hogwarts; and there’s a troll loose in the dungeons. Our heroes realize that all the strange things happening in Hogwarts have to do with Voldemort.

- Dilemma: Do Harry and his friends go into the dungeon to save the sorcerer’s stone and risk possible death and almost certain expulsion, or do they turn back and allow Voldemort to capture the stone and return to full strength.

- Climax: Holy crap, (SPOILER, if you somehow haven’t read this book) it’s Quirrel! All the conflict and questions have led to this point; we see Ron’s skills with chess and Hermione’s unusual intelligence combined with Harry’s flying skills to lead to this amazing moment, in which Harry has to make a choice: to side with evil and possibly get his parents back, or choose to continue to suffer that grief and fight the evil bad guy.

- Resolution: Harry wakes up in the hospital wing. The major issue of the story was addressed in the climax, but now, Dumbledore wraps up the few loose ends, tells Harry what happened, and shares some of the consequences of Harry’s decisions. (“What happened down in the dungeons between you and Professor Quirrell is a complete secret, so, naturally the whole school knows” is one of my favorite lines in any book ever.) Oh, and the Gryffindors Win Everything. Then, he’s heading back home, looking forward to next year, and while there are still questions and challenges ahead of him, enough has been resolved that the reader can put the book down with a contented sigh. (Or in my case, turn right back to page one and start again. Ahem.) Harry’s new normal has been established.

To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

- Exposition: We’re introduced to the town of Maycomb, to the Finch family (Atticus, Scout, and Jem), and to the setup of racism in the deep south of 1930s Great Depression America.

- Inciting Incident: Atticus, a lawyer, agrees to defend Tom, a black man, on charges of raping a white woman—placing him in direct conflict with pretty much everybody in the town, especially Bob Ewell, the father of the white woman accusing Tom.

- Rising Action, Progressive Complications: The investigation and then the trial ensues. A mob attempts to lynch Tom, until Scout diffuses the situation. Then, the courtroom scene. Ouch. Racism wins out over justice, and it looks like Tom is going to be executed.

- Dilemma: Scout must decide whether to give up hope in humanity and the possibility of true justice (like Jem) and end up jaded and mistrustful, or continue hoping that people can be good (like Atticus) and risk being naive and disappointed.

- Climax: Bob Ewell, humiliated by the trial, vows revenge, confronting Jem and Scout at night on their way home alone. In the struggle, Ewell breaks Jem’s arm. However, Boo Radley, their hermit neighbor, rescues them, finally giving Scout the chance to see him.

- Resolution: At the end of the story, Scout reaches a complicated and painful but honest conclusion: everyone is a person with good and bad to them, and injustice is unfortunately a deeply ingrained part of the system. Scout has grown in maturity, even at the cost of her innocence.

(By the way, K.M. Weiland has an incredible database of stories in which she breaks down the plots of movies and books alike. Check it out and enjoy.)

Plot Questions to Ask Yourself

So how do you achieve an amazing plot structure? There are a few simple questions to ask yourself about every scene that can help you whittle away problems and connect what needs connecting.

- For Exposition: What is “normal” at the beginning of this book? Remember, your character needs to grow and change, and the loss of this normal is part of the price paid.

- For Inciting Incident: What kind of story are you telling? Each story type has a unique type of inciting incident, and it’s good to be familiar with them. Check our inciting incident guide for all the types.

- For Rising Action: What’s at stake? What’s the cost if your protagonist blows it? If you can’t answer this, your reader won’t be able to, either. It needs to be built up enough that your reader cares. It can be good to keep a list of the issues and questions you’re creating in this section; there’s nothing more satisfying than to have all the little loose ends wrapped up later.

- For the Dilemma: What impossible choice will your protagonist face? Will they have to choose between two bad things (e.g. sacrifice or self-preservation) or two good things (e.g. love or money)? What are the consequences of that choice? What will happen if that choice doesn’t work out?

- For the Climax: How does it all come to a head in the climax? This needs to emotionally be the crux of everything you’ve built up to, and the stakes need to be in genuine danger. If there’s no real threat, then there’s no reason for your reader to care. This climax has to matter, even if it’s about something as simple as selling enough magazines to send a little girl to camp.

- For Denouement: What is “normal” at the end of this book? After the storm passes and the water calms, what has changed? If you’re writing a series, here’s where you’re establishing what “normal” will look like in the beginning of book two. (Note: you can move this step to the end, but I find it’s really helpful if you know where you’re going as you plan.)

PRACTICE

It’s time to apply this to your writing. For this lesson, you have two options for your practice:

- Create a six sentence plot outline for your story, one for each of the six elements above. Pay special attention to the inciting incident and dilemma.

- Tackle your work in progress. Take one of the components of plot (exposition, inciting incident, rising action, climax, denouement), and show that point in your story.

Set your timer for fifteen minutes and go through one of the plot exercises above.

If you are already a Write Practice Pro member, post your practice here in the Practice Workshop for feedback. Be sure to give feedback to a few other writers and encourage each other.

Not a Pro member yet? You can join us here as a Write Practice Pro monthly subscriber and see what a difference a professional writing community can make as you pursue your writing goals!

About the author

Joe Bunting is an author and the leader of The Write Practice community. He is also the author of the new book Crowdsourcing Paris, a real life adventure story set in France. It was a #1 New Release on Amazon. Follow him on Instagram (@jhbunting).

Want best-seller coaching? Book Joe here.

Best-Selling author Ruthanne Reid has led a convention panel on world-building, taught courses on plot and character development, and was keynote speaker for The Write Practice 2021 Spring Retreat.

Author of two series with five books and fifty short stories, Ruthanne has lived in her head since childhood, when she wrote her first story about a pony princess and a genocidal snake-kingdom, using up her mom’s red typewriter ribbon.

When she isn’t reading, writing, or reading about writing, Ruthanne enjoys old cartoons with her husband and two cats, and dreams of living on an island beach far, far away.

P.S. Red is still her favorite color.